The LBPD’s Drone Program: Four Drones, Zero Departmental Policy, and Yet Another Reason for the Passage of a Surveillance Equipment Transparency Ordinance

During last summer’s protests, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) had drones and AS350 helicopters in the air over 15 cities across the country collecting hundreds of hours of footage of Black Lives Matters protests. The data was fed into what DHS calls the “big pipe”—a database used by the Federal agencies and local police departments for future investigations.

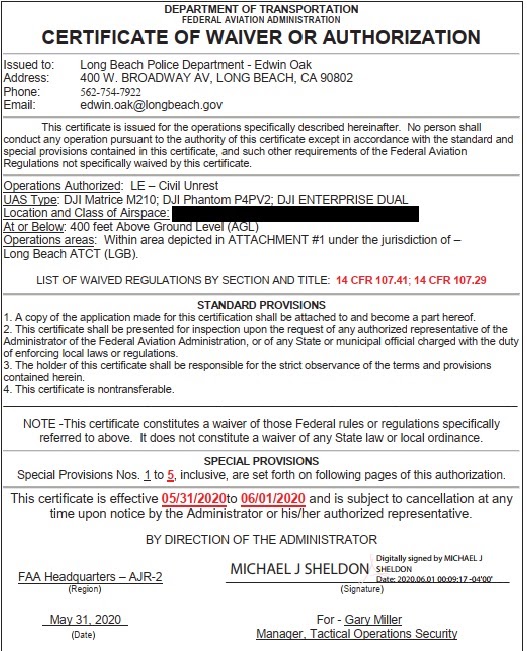

While no federal drones have been discovered in Long Beach, CheckLBPD.org has uncovered that the Long Beach Police Department (LBPD) had permission to have drones in the air on May 31 and June 1, 2020 through an emergency waiver from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). The waiver of two subsections of FAA regulation Part 107 was electronically signed by FAA representative Micheal Sheldon of FAA Headquarters AJR-2 on June 1, 2020 at 9:17 a.m.

No word yet on if there is a “little pipe” where local law enforcement shares their drone footage, but a public records request has been filed for any footage collected. It seems a strong possibility given there is a Los Angeles County “Looting Task-Force”, which has been reported to include multiple federal agencies with an eye towards federal prosecutions.

Documents obtained by CheckLBPD from a California Public Records Act (CPRA) request in July 2020 (and received in March 2021) contain an FAA waiver for the LBPD stating “Operations Authorized: LE – Civil Unrest” and covering the dates May 31 and June 1, 2020. The documents from this request, and many others, are available in the CheckLBPD.org library of CPRA request documents.

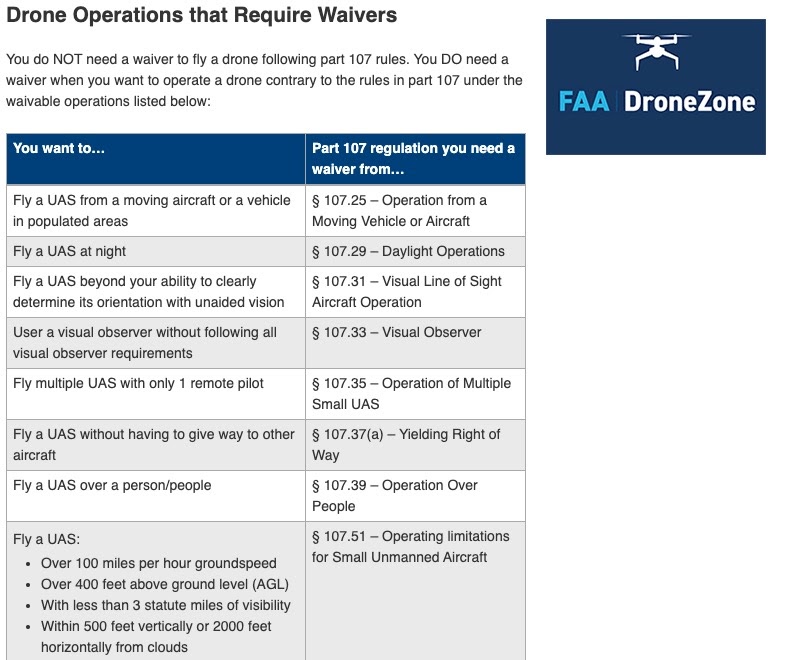

The LBPD’s FAA Part 107 waiver covers two subsections of FAA Part 107 regulation on drones, 14 CFR 107.29 (nighttime flights) and 14 CFR 107.41 (permission to fly in expanded restricted air space where there is an increased risk of collision with aircraft).

(Click Image To Open Entire Doc)

What is an FAA Part 107 waiver?

Part 107 was enacted by the FAA in 2017 to allow individuals, private businesses, and government agencies to operate drones in U.S. airspace below 400 feet. Part 107 even governs local police departments’ use of drones. Due to civil unrest the LBPD sought and received a waiver of two subsections of the law.

The two subsections the LBPD got waived May 31 and June 1, 2020 were 14 CFR 107.29, which covers night flights, and 14 CFR 107.41, which covers permission to fly in certain restricted air space where there is an increased risk of collision with aircraft (or in FAA terminology: Class B, Class C, or Class D airspace or within the lateral boundaries of the surface area of Class E airspace designated for an airport).

Those were the nights when protests were scheduled in Long Beach—with looting breaking out using the protests as cover around 5 p.m. on May 31, 2020. Shortly before 6 p.m. the LBPD issued an “unlawful assembly” order. It is still unknown what time/date the LBPD sought their FAA waiver, or the area it covered.

A 14 CFR 107.39 waiver was not granted to the LBPD on May 31 or June 1, which would have allowed them to fly over people. The documents the LBPD produced in response to CheckLBPD's public records request do not show whether the permission was sought and denied, or just never sought.

That is worth repeating, the LBPD’s waiver for drone use during “civil unrest” did not grant permission to fly over people—which is not a risk free event. If there is anything the TGIFriday's mobile mistletoe debacle should have taught us, it is drones can be dangerous—even cute ones (especially to faces).

The department did turn over the map showing the flight area the FAA granted them, but it is not very helpful.

The LBPD’s Growing Drone Fleet and Lagging FAA Approvals

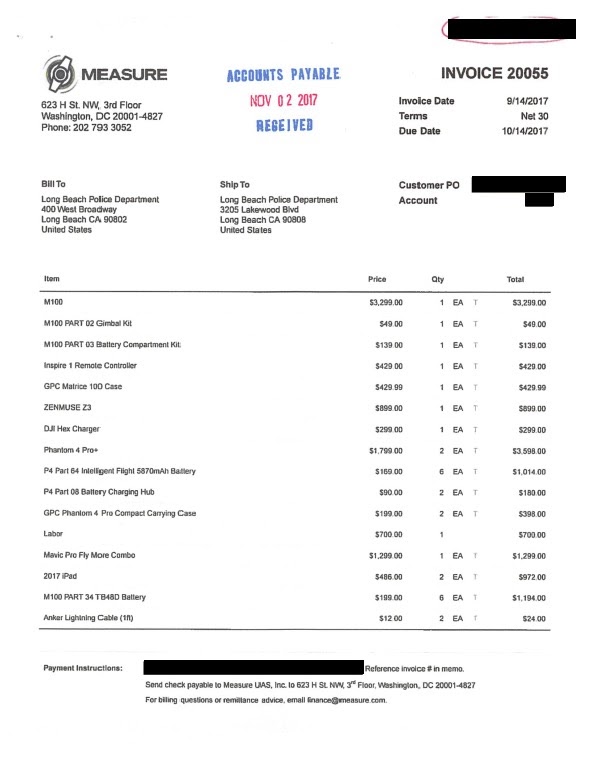

The LBPD has a small, but growing fleet of four drones with mounted-cameras. Despite purchasing its first two drones in 2017, the department has yet to develop any policy for their drone fleet. From documents produced to CheckLBPD, the Long Beach City Attorney’s Office first sought authorization for the LBPD’s drone fleet in a May 2018 letter ; this is despite the LBPD’s first drone being purchased in September 2017.

CheckLBPD’s CPRA request sought all LBPD FAA certifications and authorizations. We received documents showing that the May 2018 FAA certification request was not granted until September 2019. Prior to that, in August 2018, the LBPD wrote a letter to the Long Beach Airport addressing the “case for the airworthiness” of the DJI Matrice M100 and Phantom Professional 4 drones. It would seem the City neglected to get the approval of the local airport whose airspace they planned to use when they originally filed their FAA authorization in May 2018.

Bottom line: LBPD documents show the department bought its first drones in September 2017 and did not have FAA authorization documents in place to use them until September 2019. It is currently unknown if the drones were in use between those two dates or if there was preliminary permission granted.

Four drones appear in the inventory list the LBPD produced, but the LBPD did not produce any FAA documents certifying the two newer drones. However, the inventory list did include the “cert #” of the newer purchases.

Missing LBPD Drone Policy and their New Drone Policy Consultant

The only class of documents the LBPD failed to produce in response to CheckLBPD’s CPRA request on drones was the department’s drone policy. This is arguably a more important document than any FAA authorization because a local policy, if Long Beach had one, would be what protects the people of Long Beach’s privacy and Constitutional rights.

The LAPD got their first drone in 2017, with the Los Angeles Times headline reading “LAPD becomes nation’s largest police department to test drones after oversight panel signs off on controversial program.” The LAPD’s drone policy was drafted at the time they purchased their drones and sought to ensure that drones were used in a manner that respected individual’s privacy, safety, and Constitutional rights. The LAPD's drone policy also has specific bans on using facial recognition technology on drones and on mounting weapons on drones.

The Long Beach Police Department bought their first drones the same year as the LAPD, but the five-year old program still operates without a departmental policy. A police drone program with no outside oversight and no internal policy is a recipe for Constitutional violations (specifically of the First Amendment right to freedom of assembly, i.e. protest, and Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable search and seizure).

Surveilling peaceful protests with camera-equipped drones could certainly have a chilling effect on Constitutionally-protected right to protest. Drones are also the perfect tool for police try whittle away at our Fourth Amendment rights by expanding what is in "plain view" and reducing the public's "expectation of privacy".

CheckLBPD originally filed our CPRA request for the LBPD’s drone policy on July 23, 2020, and after three months we inquired about the documents. On Nov. 22, 2020, the LBPD replied, “your public records are currently being processed. We hope to have the review process completed before or by December 11, 2020.”

It would not be until March 2, 2021 that CheckLBPD.org received the FAA and drone inventory documents. For those wondering, the timeframe set out in the CPRA is for responses to be received in 10 days, with an available fourteen day extension. Beyond that delays are only supposed to be due to unusual circumstances. According to MuckRock.com (a site for crowdsourcing Public Records requests and sharing the documents with the public) the LBPD’s average CPRA completion time is 173 day, slightly less than it took them to produce the drone documents in this case.

The LBPD produced everything CheckLBPD asked for except the drone policy we requested. Instead of receiving the LBPD’s Drone policy, we were told the document was being withheld. The reason cited, “Preliminary Draft, withhold per Cal. Gov. Code Section 5254(a)(5)”.

That code section allows preliminary drafts of documents to be withheld “if the public interest in withholding those records clearly outweighs the public interest in disclosure.”

That is an odd denial given the policy will eventually be made public on the LBPD’s Senate Bill 978 page where they display their policy and training documents. Perhaps there is a public interest in not seeing how the sausage is made.

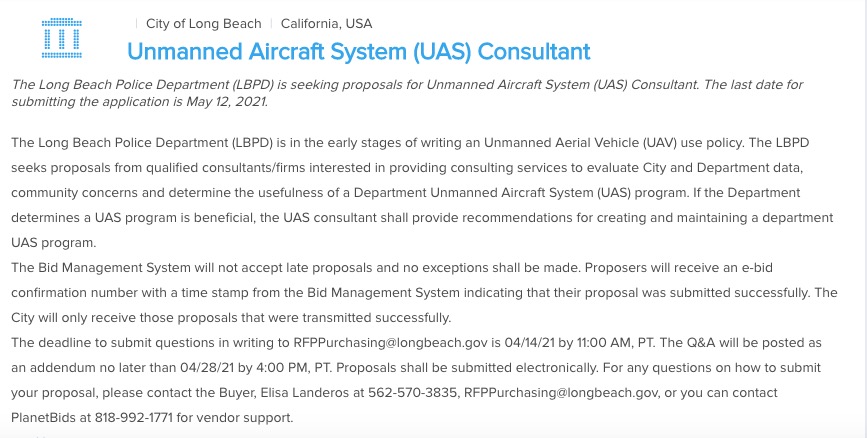

Adding to the oddness, after claiming on March 2, 2021 that the department had a preliminary drone policy it couldn’t release as a public record, it then later issued a public bid solicitation on March 31, 2021 for an “Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) Consultant” to help draft a drone policy for the department.

The job listing stated that city is in the “early stages of writing an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) use policy” and is seeking “consulting services to evaluate City and Department data, community concerns and determine the usefulness of a Department Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) program.”

In case that wasn’t clear, the LBPD claimed to have a preliminary drone policy draft it was withholding “in the public interest” and then four weeks later hired a consultant to “evaluate community concerns and determine the usefulness” of the LBPD’s drone program.

The LBPD claims they care about “community concerns”, but also responded to CheckLBPD's PRA for their drone policy by claiming the drafting process needs to be kept secret citing a law that states they may do so if the “public interest in withholding those records clearly outweighs the public interest in disclosure”.

Trusting the LBPD to determine what is in the public interest would be a lot easier if they had not gone five years without a drone policy, or if this were not the first time they used easily misused or abused new technology in secret without any departmental level policy.

Problems with Past LBPD Surveillance Policies

In a past investigation CheckLBPD determined that the LBPD ran a facial recognition program for over a decade without ever drafting a policy (a story you can read about in this CheckLBPD report, part of our ongoing investigation into the Surveillance Architecture of Long Beach.) The LBPD had denied the existence of a facial recognition program for years to past CPRA requesters and in response to press inquiries last summer. While the LBPD has not yet drafted an official facial recognition policy in response to CheckLBPD uncovering the program, they have made one major change.

Last year CheckLBPD filed a series of increasingly specific CPRA requests that uncovered the LBPD was using free trials of two flawed private facial recognition databases. Months after our initial request, and before the LBPD produced the documents showing the full scope of the program, Investigative Bureau Deputy Chief Herzog issued a September 2020 order prohibiting the use of the private Clearview AI and Vigilant Solutions FaceSearch databases for investigative purposes. It is still unknown if anyone at the Deputy Chief or above level had known about the free trials before cancelling them.

The only time the LBPD seems to draft a surveillance technology program policy is when it is required. The LBPD purchased a Stingray cell-phone interception device and used it for over two years without policy, until the state passed Senate Bill 741 requiring all departments using cell site simulators to have a public policy by Jan. 1, 2016. Senate Bill 34 required all agencies using ALPR technology to have a policy in place by Jan. 1, 2016. This law is likely the only reason the LBPD’s Automated License Plate Reader program has a departmental policy, and that program was started in 2006.

When drafting these policies, instead of involving the community or its elected representatives, it seems the LBPD relied on a corporation. From mid-2014 to the end of 2015 the LBPD spent $33,000 with Lexipol—the leading drafter of police policies nationwide. The dates of these payments correspond with the period the LBPD would have been drafting its ALPR policy and the policy has all the looks of a Lexipol document—including phrases drafted by someone from out of state. For example, in California, we use the term Public Records Act not Freedom of Information Act. However, the LBPD’s original ALPR Special Order goes with the phrase “the jurisdiction's freedom of information act”, instead of citing the CPRA.

Relying on a corporation to draft a police policy removes the community from the process and creates a disconnect between a department and its own policies. It results in window dressing, not real oversight. In the article “Meet the Company the Protects the Cops”, MotherJones examines the role Lexipol plays in enabling incidents of excessive force and helping the officers who commit them go unpunished.

The reliance on corporations to draft police policy and training documents has another consequence—serious implications for governmental transparency.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation filed suit last week against the California Police Officer Standards and Training (a public agency) for training documents related to facial recognition and Automated License Plate Readers. The agency is required to make these documents public under Senate Bill 978. California P.O.S.T. is fighting making the documents public—claiming they cannot release the documents as California law requires because of the private company’s copyright on the training. This lawsuit will decide whether the public's right to know how police officers are trained can be defeated by a corporation putting a copyright on the training.

Past LBPD Surveillance Scandals and How the Corporations that Caused Them Were Rewarded by the City, or Why Privatizing Police Oversight in Long Beach Will Never Work.

The process of letting an unaccountable private consultant draft our city’s drone policy is likely to be as useful as the sham “independent” investigation the city carried out regarding the TigerText scandal—a scandal exposed by Stephen Downing of the Long Beach Beachcomber. CheckLBPD dug deep into the city’s TigerText report using the program's metadata and other public records. Our extensive investigation into the TigerText metadata showed the report was nothing more than a cover-up, and that the law firm that carried it out was subsequently rewarded with millions in city contracts.

Despite its cost, the LBPD’s ALPR policy is so flawed you’d have to read five articles to get caught up with how flawed it is:

"LBPD Dragnet Snags the Innocent" (Beachcomber)

"City Council to Decide Whether to Buy Controversial License Plate Readers" (FORTHE)

“Police in Pasadena, Long Beach pledged not to send license plate data to ICE. They shared it anyway” (LA Times)

“Experts Say ICE Likely Still Able to Access LBPD License Plate Data; Local Elected Officials Remain Silent on Issue” (FORTHE)

"ACLU Alleges LBPD Use Of License Plate Reader Data Illegal” (Beachcomber)

CheckLBPD has been involved every step of the way—in fact, assisting Stephen Downing on his article on the LBPD’s misuse of ALPR at this summer's protests was what inspired the CheckLBPD.org project.

While investigating how the LBPD flagged the license plates of two innocent protestors as potentially armed felons in a nationwide database (leading to traumatic, potentially deadly encounters with police), Check LBPD uncovered documents that showed the LBPD had been violating state and local law by sending the geolocation data from its ALPR program directly to Immigrations and Customs Enforcement.

The LBPD was sharing over 50 million pieces of data on Long Beach residents, over 100 pieces of data for every person in the city. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) had this data during the ten most active months of the Trump Administration's civil deportation push leading up to the 2020 election. Internal ICE ALPR program documents show ICE was using ALPR data as part of their administrative deportation efforts. ICE used the data to track “patterns of life” and to find new addresses on targets they had lost by running their license plate numbers or those of their family members.

The LBPD contributed over 50 million geolocation points dating back two years to the pool of data ICE was using. The LBPD only stopped the illegal data sharing after FORTHE published an article in November 2020 using the documents CheckLBPD.org uncovered while investigating the protest misuse. The LBPD’s sharing of data with ICE violated the Long Beach and California Values Act—which prohibits local police from cooperating in the administrative deportation of non-criminal immigrants.

Perhaps if our elected representatives had been more involved with ALPR policy drafting and oversight, mistakes like this could have been avoided. The drafters of the Long Beach Values Act never made any mention of ALPR or any of the other surveillance technologies that should have been covered by the city’s Values Act.

Instead we had Mayor Robert Garcia's July 2019 statements (in English and Spanish) that “the police department will not cooperate with ICE in civil immigration arrests and enforcement operations and that the federal organization does not have access to LBPD’s internal data.”

In reality, just five months later the LBPD would begin sharing access to the database ICE was most eager to access, license plate tracking data. This was a blatant violation of both the Long Beach and California Values Act. The LBPD is not even supposed to be collecting sensitive data under the Long Beach Values Act, let alone sharing it with ICE.

The city spent years telling immigrants they could trust their local government, then failed them at the most critical time. For ten months during the Trump Administration's 2020 attempt to win reelection using immigration as a wedge issue, the LBPD was sending ICE the data its civil deportation squads most wanted. Despite what Mayor Garcia said, the lack of any outside oversight of the LBPD meant his words were nothing more than hollow promises he had no business making.

It should not have come as any surprise that the LBPD would cooperate with ICE. The LBPD has been an eager ICE cooperator in the past, even giving three ICE and CBP agents their own log-in credentials on the LBPD’s Vigilant Solution ALPR database. The Electronic Frontier Foundation uncovered that three ICE and CBP agents conducted over 850 searches using their LBPD credentials in 2016—with access only cut off just before the California Values Act was passed.

How Long Beach Rewards Corporate Incompetence

While Long Beach only has a $25,000 per year contract with Vigilant Solutions for ALPR services, ICE’s last contract was worth $6.1 million to the company. In a 2019 report by the California State Auditor, Vigilant Solutions was criticized for running a poorly-designed database that made it more likely for local police to share their data with immigration authorities in error.

ICE documents uncovered by the ACLU using the Freedom of Information Act show the Vigilant Solutions design problems the State Auditor pointed out might not be so accidental—with Vigilant Solutions’ employees training ICE agents on the most effective ways to request data from local police. In fact, the ability to get local police department data was marketed as a selling point of the program.

Despite all these problems, and the fact that other jurisdictions like Alameda have boycotted Vigilant Solutions for its work with ICE, the Long Beach City Council voted unanimously to approve a new $400,000 purchase of ALPRs from the company. The purchase was approved as part of the consent calendar, meaning no public comment or debate was allowed on the agenda item. The council approved the contract despite the publication of FORTHE’s article pointing out the ICE data sharing, and City Council meeting comments challenging the appropriateness of handling the item as part of the consent calendar.

When the LBPD illegal data sharing was uncovered by CheckLBPD and FORTHE, the LBPD blamed an error on a “private contractor.” While the department did remove ICE from its data sharing partners after the FORTHE article, it neither took steps to make sure it would not happen again nor to cut off the numerous other avenues ICE had to gain access to LBPD data.

Instead of making any real change, the LBPD sought to sweep it under the rug with a little help from the Mayor’s office.

The city’s “investigation” (which did not examine if the General Dynamics contractor it put in charge of its ALPR system had been trained on the Long Beach or California Values Acts, or even uncover the fact that he had been previously trained by ICE). Nevertheless the LBPD announced it had identified and solved the problem.

In response, James Ahumada, a spokesman for the mayor said, “the Mayor and the City Council have made it clear that the LBPD may not share civil immigration information with ICE. The chief fixed this error a month ago and is working to ensure privacy and alignment with SB54 and the Long Beach Values Act.” That is a statement that could not be further from the truth as CheckLBPD’s upcoming deep dive into the City’s ALPR program will explain.

The LBPD’s December 2020 claim to have identified and solved the ALPR problem triggered a slew of PRA requests on the LBPD from CheckLBPD. By the time CheckLBPD uncovered and confirmed the identity of the contractor (an employee of General Dynamics) the City Council had already unanimously approved a new five year contract for the company as the last item on a lengthy consent calendar not open to public comment or debate.

After Vice-Mayor Rex Richardson made a motion and Councilmember Zendejas seconded it, the council approved the five-year contract for General Dynamics at $379,000 per year on April 6, 2021 solely on the recommendation of Chief Luna—apparently the only voice they wanted to hear on the matter. The fact that this was the contractor responsible for adding ICE to the LBPD data-sharing partners was not mentioned.

The first two years of the new General Dynamics LBPD contract are guaranteed; after that the City Manager is in charge of renewals. Hopefully, the unelected City Manager will also put himself in charge of making sure these federally-trained contractors get some training on local and state law, so we don’t have any more data-sharing “accidents” that put the city in violation of its own Values Act ordinance.

Chief Luna would have known when he recommended General Dynamics (a company that both built child detention centers during the Trump administration and helped the government to fill them) that the company was the reason Long Beach was in violation of both Values acts for ten months. Instead of pushing for accountability from the contractors he oversees, he pushed through a lucrative renewal of their contract before the truth could be publicly known.

Independent Oversight > Part-time City Council Subcommittee

While people in Southern California rarely point to the Los Angeles Police Department as a model to follow for police reform or transparency, the LAPD is years ahead of the LBPD.

One reason is Los Angeles has an empowered, civilian-staffed, independent police oversight commission. Meanwhile, Long Beach relies on City Councilmembers who are only paid as part-time workers and all have other jobs. Many of those who have served on the Public Safety Committee over the years have been beneficiaries of Long Beach Peace Officer Association lobbying and campaign donations, with police union funding of political campaigns being a problem in Long Beach.

The LAPD also has an Office of Constitutional Policing staffed by a respected former U.S. Attorney with a deep background in Constitutional Law. The LBPD started their own version of an Office of Constitutional Policing, although instead of an expert on the Constitution it is staffed by an LBPD Lieutenant.

The LBPD created the Office of Constitutional Policing last July as their contribution to the Framework on Reconciliation with the stated goals of “ensuring the Department is up to date with best practices in policing, legal mandates, and community expectations” and “guiding the expansion of data analytics for accountability and transparency.”

The LBPD’s Office of Constitutional Policing has yet to announce a single policy change or finding. By way of contrast the CheckLBPD.org campaign of Public Records Act requests has lead to five separate policy changes at the LBPD (Stingray policy updated and posted SB 978 policy document collection, use of private facial recognition databases stopped, ICE ALPR data-sharing stopped, departmental policy on Excited Delirium redrafted, spit hood policy redrafted, and now a drone policy is in the works). It is amazing what you can trigger when you ask the right questions in a forum where a response is required.

CheckLBPD.org is even ahead of the Office of Constitutional Policing when it comes to the promised “data analytics” they promised—with two separate data dashboards already available to the public and more to come. We made a data dashboard of all LBPD purchases including vendors and spending amounts going back to 2013 which became surprisingly useful in uncovering the corporate proxies the LBPD uses to violate our privacy rights. We also made a data dashboard of the 261,000 pieces of TigerText metadata to better understand the violations of the Due Process clause of the Fifth Amendment implicated by the use of the TigerText disappearing messaging app by hundreds of the LBPD’s top officers and detectives.

Future projects will involve the department's internal "use of force" data we obtained, as well as the department's Racial Identity Profiling Act (RIPA) data.

The Best Solution to this Mess is a Surveillance Equipment Transparency Ordinance for Long Beach

The LBPD has shown over and over again that it cannot be trusted to oversee its acquisition or use of technology. Currently, the only factor in whether or not the City Council is required to approve a new police technology is the technology's cost. That is a flawed system because cost and the risk for Constitutional violations are not linked in any way.

The worst program the LBPD has ever used is Clearview AI, a program literally designed by white nationalists as an “algorithm to ID all the illegal immigrants for the deportation squads.” The LBPD used the Clearview AI database of images, some illegally-scraped from social media, on a free trial basis for two months. Their communications with the company even talked of the “success” officers had with it, meanwhile no records were kept of its use.

The LBPD also secretly used a free trial of Vigilant Solutions FaceSearch, a less unethical program that relies on the police uploading the mugshot databases and is owned by Motorola instead of a who’s who of the Alt-right.

Examining the litany problems related to the department's use of secret, policy-less surveillance technology, one thing becomes clear there is a severe lack of transparency and accountability related to technology use.

Long Beach needs a Surveillance Equipment Transparency Ordinance that requires all new surveillance purchases to be approved by a public vote of the City Council after an extended period of public comment during which the LBPD is required to be truthful about how the programs will affect the public. This would mean no more surveillance expansion by consent calendar based solely on Chief Luna’s recommendation.

The LBPD would also be required to disclose all existing surveillance technologies and file annual reports with the city on their programs. This would allow the public and City Council to insist that the department draft policies to make sure their technologies are not abused. Ideally, surveillance policy drafting would be taken out of the hands of the LBPD and its corporate contractors.

These flawed surveillance programs had Chief Luna’s stamp of approval; the city needs to stop relying solely on his judgment for the future expansion of its surveillance apparatus. Under his leadership the department has already shown a penchant for favoring technology that results in racially-biased arrests in other jurisdictions. His poor supervision of the contractors he put in charge of the department’s surveillance apparatus caused Long Beach to be in violation of the Long Beach Values Act for ten months last year.

A Surveillance Equipment Transparency Ordinance would mean the city no longer has to rely solely on Chief Luna to manage the surveillance architecture that he has shown, time and time again, to either be unable or uninterested in managing. There have been so many repeated mistakes related to the LBPD surveillance program that allowing it to continue unchanged is courting disaster. It has endangered lives, violated rights, and literally caused Long Beach to break the Long Beach Values act. If that is not a wake up call, what is?

The city needs to stop trusting Chief Luna’s recommendations and judgment in surveillance. Remember, this is a police chief who once approved a Thin Blue Line Flag challenge coin for the department and on the section on the form where it asked if there were any potential controversies he wrote: “none.”

Perhaps the nine members of the City Council should stop trusting that judgment. After all, Chief Luna recommended the council award the contractor who shared 50 million pieces of geolocation data with ICE on “accident” with a new $1.8 million contract—which they approved unanimously without question or allowing public comment.

If the City Council allows this situation to continue they are nothing short of responsible for whatever happens next. Maybe next time the LBPD wrongly flags someone in an ALPR database the police in other jurisdictions won’t just traumatize them at gunpoint, but with gunshots.

The LBPD’s reckless surveillance practices need to stop and the only way to do that is with outside oversight. Action is needed now, before even more of our rights are violated, or someone gets killed because the LBPD does not think of the consequences of labeling the wrong person as an armed felon in an ALPR database.

A Surveillance Equipment Transparency Ordinance had been proposed as a state-wide law in Senate Bill 21, which stalled in 2017. Had it passed, it would have required a public approval process for all local surveillance purchases and biennial transparency reports covering the cost, use, and effectiveness of the technology.

However, there is no reason to wait for the state to pass a version—ten cities have passed their own local Surveillance Equipment Transparency Ordinances including San Francisco, Oakland, Berkeley, Davis, and Palo Alto, along with Bay Area Rapid Transit and the entire county of Santa Clara.

It’s time for Long Beach to stop being a leader in surveillance abuse and join the growing list of California cities that have passed a Surveillance Transparency Ordinance.

Do you have any information on LBPD surveillance systems you’d like to share? Contact us at greg@checkLBPD.org (encrypted through protonmail on our end).

This article was written by Greg Buhl, a Long Beach resident, attorney, and lead researcher at CheckLBPD.org

Follow the CheckLBPD project on Twitter or Instagram: @CheckLBPD