The Surveillance Architecture of Long Beach: A Decade of LBPD Facial Recognition Technology Use with Inadequate Policy, Oversight, and Transparency (Abridged Version)

This is an abridged version of a longer exposé that is three times this length. As this is a complex topic that has not been explored in Long Beach, even this version is about a 15 minute read. Those with a personal or professional interest may prefer the added details in the longer version, however both versions capture the essential facts.

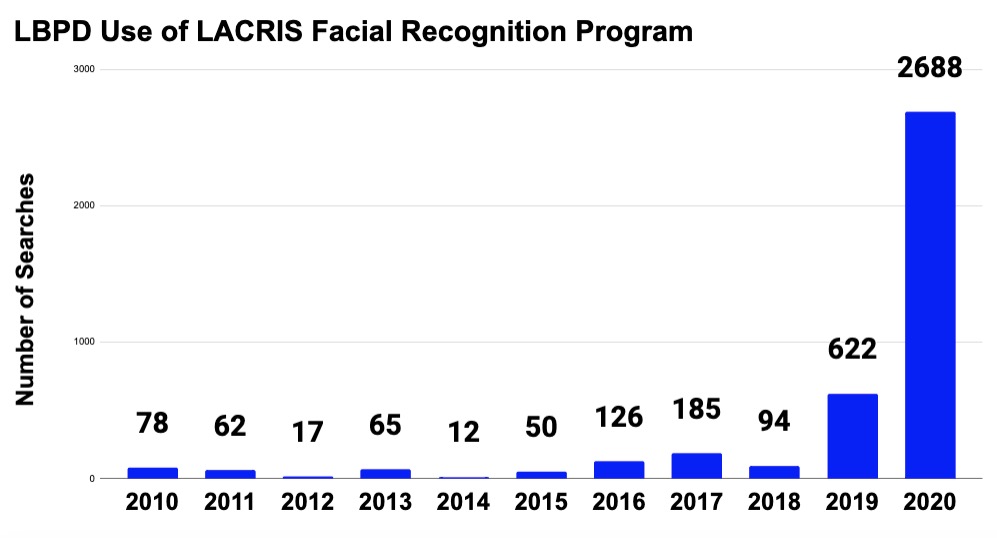

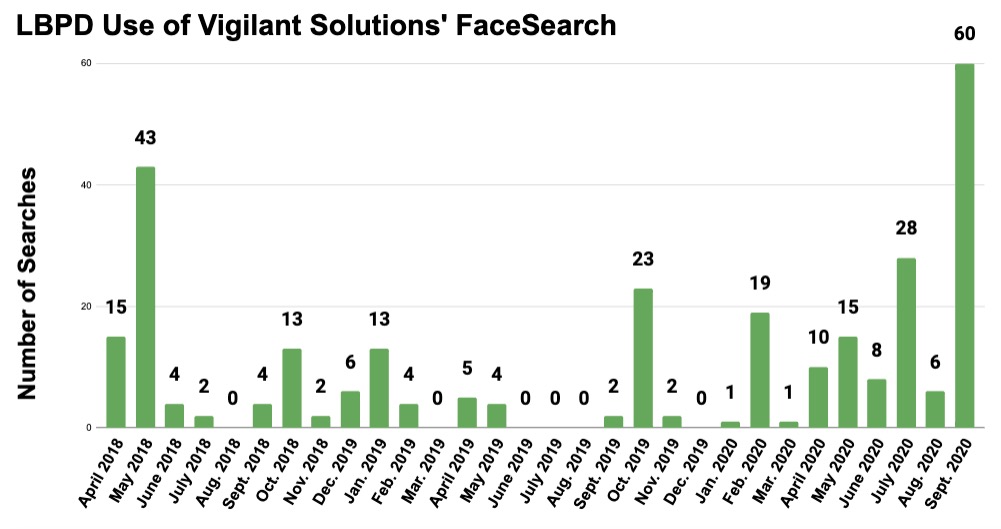

The Long Beach Police Department has used facial recognition technology since 2010—with the department having access to three different investigative facial recognition databases. The government-run Los Angeles County Regional Identification System (LACRIS) has been used since 2010. Vigilant Solutions' FaceSearch and Clearview AI have only been used in recent years on extended free trials.

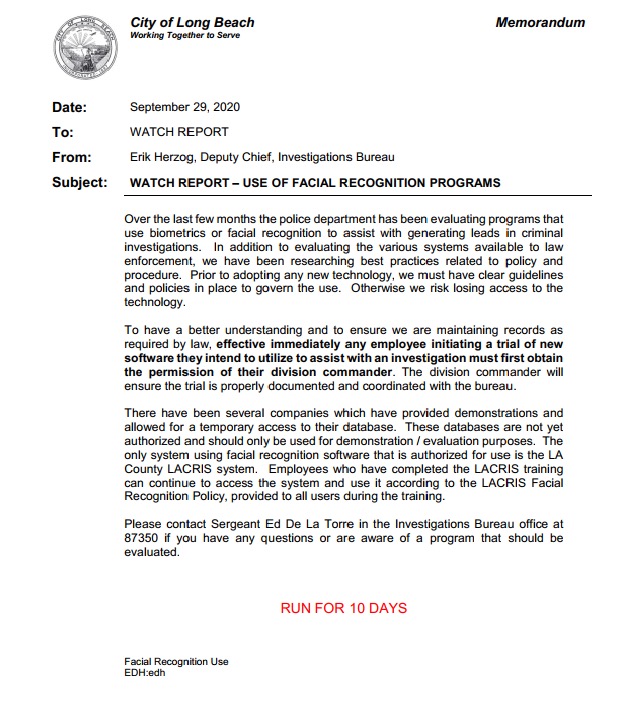

Until September 2020, there was no LBPD policy to guide the use of facial recognition. The policy that is in place now appears to be a placeholder drafted in response to inquiries made for this investigation. Right now, the closest the LBPD has to a facial recognition policy is the watch report on facial recognition and the LACRIS policy they agreed to as a condition of access. LACRIS encourages police to go beyond that minimal policy and to adopt an official local policy—even supplying a template.

Although facial recognition technology is not new, media coverage has increased recently as the technology becomes more integral to investigations—both nationally and locally. Even large departments such as the Los Angeles Police Department managed to keep their use of facial recognition under the public's radar for over a decade. In September, the L.A. Times ran a story about the LAPD's use of LACRIS in 30,000 cases since 2009, its first coverage of the program.

The LAPD has approximately 9,000 officers, meaning that the department conducted 3.3 searches per officer since 2009. The LBPD has over 800 sworn officers and conducted 4,289 searches since January 2010, or about 5.3 per officer over a similar time period. That means the LBPD used the system about 60% more often than the LAPD, adjusted for department size.

38 LBPD officers had access compared to 300 LAPD officers, which means the LBPD had a higher percentage of officers using facial recognition. However, that does not explain all of the 60%. The LBPD would also have been running more searches per officer with LACRIS access.

As interesting as the above figures are, what might be revealed in future Public Records Requests (PRA) requests is even more interesting. The 100-plus LBPD FaceSearch searches that occurred following the May 31 protests and looting seem likely related to the LBPD's Looter Task Force, but the 2,688 LACRIS searches in 2020 are not as easily explained. So far the LBPD has only produced use aggregate use figures by year for LACRIS.

That is over 2,000 more than the previous year, which itself was abnormally high. They cannot be as easily explained away as searches of potential looters since the highest estimate of the number of potential looters made by the LBPD was 300, with 2,000 closer to the total number of protestors. Indiscriminately running facial recognition searches on protestors would be a violation of the 1st Amendment and is forbidden by many police department's facial recognition policies on such grounds.

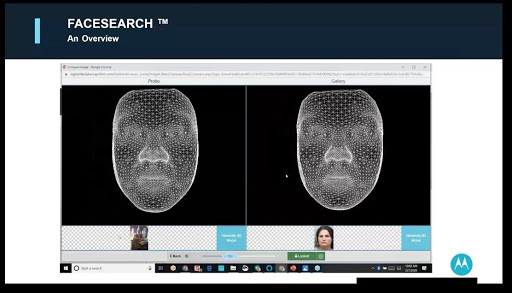

While the LBPD used Vigilant Solutions' FaceSearch for two and a half years before use was curtailed last month, it seems the first training conducted on the program occurred just days before the department stopped using the program. While many previous PRA requests for facial recognition have failed to return any training documents or materials, a response CheckLBPD received Oct. 22, 2020 produced a Sept. 24, 2020 hour-long training presentationmade to the LBPD by Vigilant Solutions' Customer Success Manager (and retired LBPD Lieutenant) Chris Morgan.

Vigilant Solutions' FaceSearch LBPD Training Session conducted by Chris Morgan, Vigilant Solutions Customer Success Manager and former LBPD Lieutenant on Sept. 24, 2020

It is unknown what triggered this FaceSearch training session, but it did follow a series of detailed PRA requests made for this investigation regarding FaceSearch training and record keeping. In the presentation, Morgan mentions the current lack of LBPD policy on facial recognition but states, "we are working with the folks to get that dialed-in." From the context, “we” would be Vigilant Solutions” and “the folks” would be the LBPD top brass. Morgan said he expected the LBPD to issue a special order on facial recognition soon with guidance on how to use the technology.

RECENT LBPD WATCH REPORTS AND SPECIAL ORDERS

Days after Morgan's presentation, the department would issue a Sept. 29 Watch Report with the subject line “Use of Facial Recognition Programs,” that would suspend the department's use of free trials of FaceSearch, Clearview AI, and any other facial recognition besides LACRIS. It is unknown if a special order has been issued or is being drafted; however, the collection of training documents and special orders posted by the LBPD to comply with S.B. 978 does not yet include a special order related to facial recognition as of Nov. 13, 2020.

Morgan spends about half his presentation addressing what he terms "myths and falsehoods" promoted by "privacy advocates" such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). Unfortunately for those attending the presentation, many of the arguments Morgan made were not true, or were based on a misunderstanding of the point he was responding to. There is a lot to say about what was said in that training session, which is in part how the full version of this report reached over 10,000 words.

CheckLBPD interviewed Dave Maass of the EFF for this report. Regarding this type of training he said, “too often, police are making decisions about technology in private meetings with vendors, who tell them all the potential miracles the technology can generate without telling them about the potential risks. It's important that the community and elected officials have a say and that these decisions are made in the sunlight. Justice requires this kind of transparency."

This was something Maass said before either of us knew the Vigilant Solutions' LBPD training session recording existed and would be made a public record. However, he described that session accurately nonetheless. If you are curious about how accurately, then the full version of this report is for you.

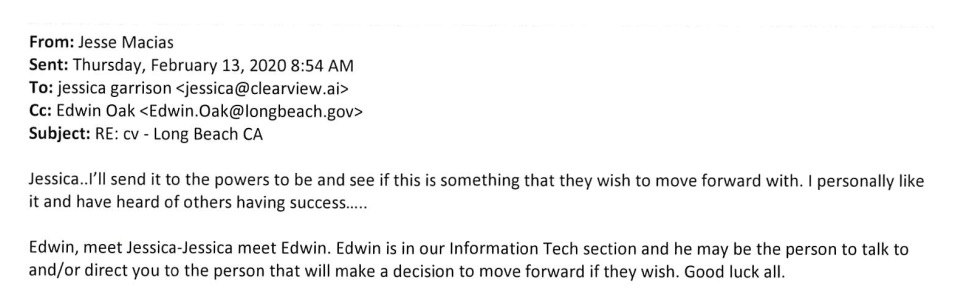

The documents received from the department show the commercial facial recognition databases may not have only been used it for evaluation purposes. Investigators emailing the company about having success with Clearview AI. The programs have little oversight or recording of use that would be expected if a department was evaluating a new technology. The length of time and pattern of use of Vigilant Solutions' FaceSearch suggests investigators saw it more as an investigative tool than a new technology that was only being evaluated.

We showed the watch report to Mohammad Tajsar, a Senior Staff Attorney at the ACLU of Southern California, who said he thought it "suggests that members of the LBPD have been inappropriately using trial evaluations of facial recognition products to conduct searches of individuals in ongoing investigations, and not properly documenting the searches in internal records."

He added that while "it is not clear what 'maintain records as required by law' refers to," it may be the Brady requirement to disclose exculpatory evidence in criminal trials or "other internal rules regarding investigative reporting requirements, internal affairs investigations, or audits."

According to Dave Maass of the EFF, who was interviewed for this investigation before the LBPD's policy change, "free trials are often a backdoor for police to adopt new technologies without oversight. Surveillance shouldn't be treated like a subscription to a wine of the month club."

Overview of the LBPD's Three Facial Recognition Systems

The L.A. County Sheriffs oversee LACRIS, and it serves 64 local police departments in L.A. County. Its facial recognition database uses information from booking photos from county and local jails and offers biometric identification for tattoos and fingerprints. LACRIS was created in 2009—with the LBPD using the system since 2010.

FaceSearch™ is made by Vigilant Solutions Inc. (recently acquired by Motorola), which also runs the LBPD's Automated License Plate Reader (ALPR) system. That system scans 24.7 million license plates a year in Long Beach. FaceSearch is a 2014 addition to Vigilant Solutions' bundle of surveillance products. FaceSearch has been able to compile a nationwide gallery of millions of faces from mugshot databases uploaded to its servers by local police departments, as well as photos from CrimeStoppers and other websites related to criminal justice, like Megan's Law or sex offender registries.

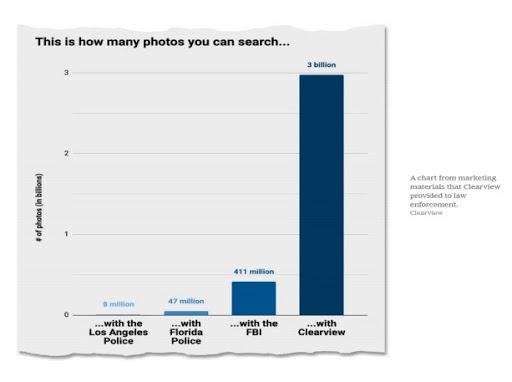

Clearview AI is a different kind of facial recognition company—not because of its search algorithm, but due to the ethical gray area they inhabit and the invasive database they have created. Clearview AI has data-scraped 3 billion images from public social media posts, regular media, personal blog pages, and sites like meetup.com—sometimes in violation of those site's terms of service. If you have any online presence, there is a good chance you are already in Clearview AI's database. You can find out if you are in their database and remove yourself from it using the California Consumer Privacy Act, a process to be discussed in more detail in our upcoming article focused on Clearview AI.

Clearview AI CEO/Co-founder, and those involved with the company's creation and growth, have extensive, recently uncovered links to alt-right extremists and actual neo-nazis. People associated with the company have made many public racist, anti-semitic, and misogynistic comments that were just uncovered in August. One described his job as "building algorithms to ID all the illegal immigrants for the deportation squads."

What may have just been a dream back when that statement was made in 2017, has recently become a reality. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) signed a contract with Clearview AI, paying them $224,000 on Aug. 12 for "Clearview licenses." Clearview AI has also demonstrated an unsettling focus on journalists who have investigated the company and has been credibly accused of using their tools for political opposition research on behalf of conservative candidates.

ISSUES WITH PAST LBPD FACIAL RECOGNITION PUBLIC RECORDS ACT REQUESTS

What CheckLBPD found in Long Beach is very similar to what the L.A. Times’ reported about LAPD use of facial recognition, specifically “widespread use stood in contrast to repeated denials by the LAPD that it used facial recognition technology or had records pertaining to it."

The LBPD admitted to using facial recognition technology once in a 2017 PRA response to a journalist with MuckRock, while also claiming to have no responsive documents regarding contacts, policy, or training. However, in 2019 the LBPD denied having any responsive documents to two separate requests. The first was a professionally-drafted PRA request on facial recognition from the Aaron Swartz Day Police Surveillance Project responded to in February 2019. The second was an equally well-drafted PRA request from Freddy Martinez of the Lucy Parsons Lab in July 2019.

Steve Downing of the Beachcomber also filed a comprehensive request for facial recognition documents this summer, but after a 70-day delay, only received the same six Clearview AI documents obtained by CheckLBPD.org. These documents only show a Clearview AI free trial starting in December 2019 and nothing to indicate the LBPD had two other facial recognition programs that were still ongoing.

CURRENT MORATORIUM ON FACIAL RECOGNITION ON BODY CAMERA FOOTAGE

A 2018 ACLU study was one of the driving forces behind the passage of A.B. 1215—California's three-year moratorium on police body cameras and data collected by body cameras currently in effect.

A.B.1215 states facial recognition "has been repeatedly demonstrated to misidentify women, young people, and people of color and to create an elevated risk of harmful "false positive" identifications." These concerns are why facial recognition use on police body camera data is banned until 2023. The assembly bill states this is because using the technology on police body cameras would "corrupt the core purpose of officer-worn body-worn cameras by transforming those devices from transparency and accountability tools into roving surveillance systems."

The desire to guard against the corruption of the accountability purpose of police body cameras resulted in a broad ban that prevents law enforcement "from installing, activating, or using any biometric surveillance system in connection with an officer camera or data collected by an officer camera."

A.B. 1215 is the only law governing facial recognition in Long Beach. Although, over a dozen other jurisdictions have adopted city or county level laws banning, limiting, or regulating the use of the technology—including San Francisco, Boston, Oakland, Berkeley, Santa Cruz, Jacksonville, MS, and both Portlands.

STUDIES SHOWING THE PROBLEMS, INACCURACIES, AND BIASES IN FACIAL RECOGNITION

Numerous studies conducted by governments, non-profit organizations, and universities have found accuracy issues. Tajsar of the ACLU says, "facial recognition is inaccurate and should not be used given its well documented and researched accuracy concerns."

These studies have built on each other and been the driving force behind much of the legislation on facial recognition that has been passed across the nation.

The most definitive study on the technology was conducted in December 2019 by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), a U.S. government physical science laboratory. NIST ran "18.27 million images of 8.49 million people through 189 mostly commercial algorithms from 99 developers." The study looked at "false positives" by demographic groups and found some systems were 10 to "beyond 100 times" more likely to misidentify a Black or East Asian face. Women were misidentified more often than men, with Black women the most misidentified group.

The NIST study was inspired by a 2018 report from the Georgetown Law School Center on Privacy and Technology called The Perpetual Line-up: Unregulated Police Face Recognition in America that found that half of all American adults were already in law enforcement facial recognition databases. Georgetown found that the way police use facial recognition can replicate past biases. The report found that "due to disproportionately high arrest rates, systems that rely on mug shot databases likely include a disproportionate number of African-American."

When future arrests are then made by searching databases created by past arrest, the over-policing of communities of color continues—just with a digital facade.

Another complaint frequently made by experts is that police have increasingly used the technology to solve petty crimes—without any resulting improvement in public safety. The current trend is that those with criminal records committing property offenses captured by surveillance cameras are low hanging fruit that gets picked over and over—while harder to solve and prosecute crimes consequently get less attention.

The Georgetown Law School report found widespread adoption and frequent use of facial recognition technology by police. The report also found problems such as lax oversight, failure to safeguard Constitutional Rights, failure to audit for misuse, missing Brady disclosures to defense counsel, and police using the technology to investigate petty crimes.

The report summarized the situation as "law enforcement face recognition is unregulated and in many instances out of control." In Long Beach, that is undoubtedly true. The LBPD can not even say how many searches it ran on Clearview AI, let alone the reason for the searches or what was done with the results.

Long Beach’s lack of policy to guide its facial recognition use is not unusual. Georgetown discovered that only 4 of the 52 departments found to be using facial recognition technology had policies governing its use, and only one of those included a prohibition on using facial recognition to track individuals engaging in political, religious, or other protected free speech. Nine of the 52 departments claim to log and audit their officers' face recognition searches for improper use—though only one was willing to prove this with documentary evidence.

The LAPD was surveyed for this study but supplied an incorrect response regarding the existence of their facial recognition program—one of many inaccurate LAPD public statements on facial recognition covered in the L.A. Times reporting.

Georgetown Law's "Perpetual Line-Up" study built on an 2012 FBI-authored study that found "female, Black, and younger cohorts are more difficult to recognize for all matchers used in this study."

Another source of misidentification described is when the database does not contain the face being searched for, and the system produces its closest match anyway—which then can put that innocent individual in the position of having to prove their innocence.

Research by M.I.T. and Stanford on facial recognition programs from major companies found that while white men never face an error rate higher than 0.8%, the error rates for dark-skinned women were hitting 20 and 38 percent with some programs. Separate studies from the ACLU on state and federal legislators' photographs have found accuracy issues along racial and gender lines.

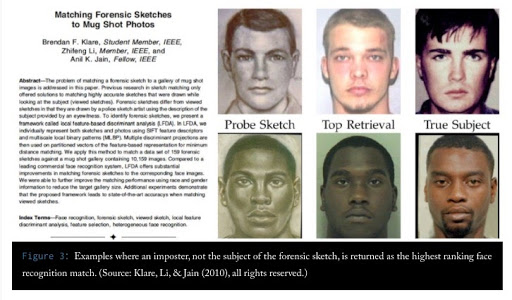

"Garbage In, Garbage Out" is the title of a second Georgetown Law School study on facial recognition done in 2019. It describes some of the questionable ways police have used facial recognition. Police have submitted celebrity photos to facial recognition programs because they did not have a suspect's picture, but did have a description that the suspect looked like a particular celebrity or athlete.

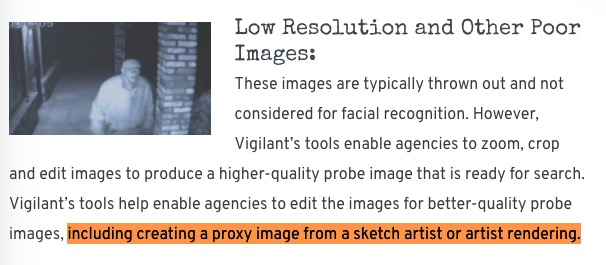

It is not yet known if Long Beach runs facial identification on artist sketches or uses celebrity doppelgängers, but there is no technological or policy limit that would stop them. As will be discussed in the Vigilant Solutions specific article, the company once advertised the ability to run sketches through its facial recognition database—only removing the content from its website after it was mentioned by Georgetown Law in "Garbage In, Garbage Out.

It is currently unknown in what types of cases the LBPD used Vigilant Solutions' FaceSearch and whether they had any "success" as they did with Clearview AI—before use of the programs were curtailed by the watch report.

FALSE ARRESTS BASED ON FACIAL RECOGNITION MISMATCHES

2020 will leave its marks in the history books for a lot of reasons. Something that might get lost in the endless stream of environmental, political, and public health stories is that 2020 marks the first civil lawsuit over a wrongful arrest based on a mistaken facial recognition algorithm match.

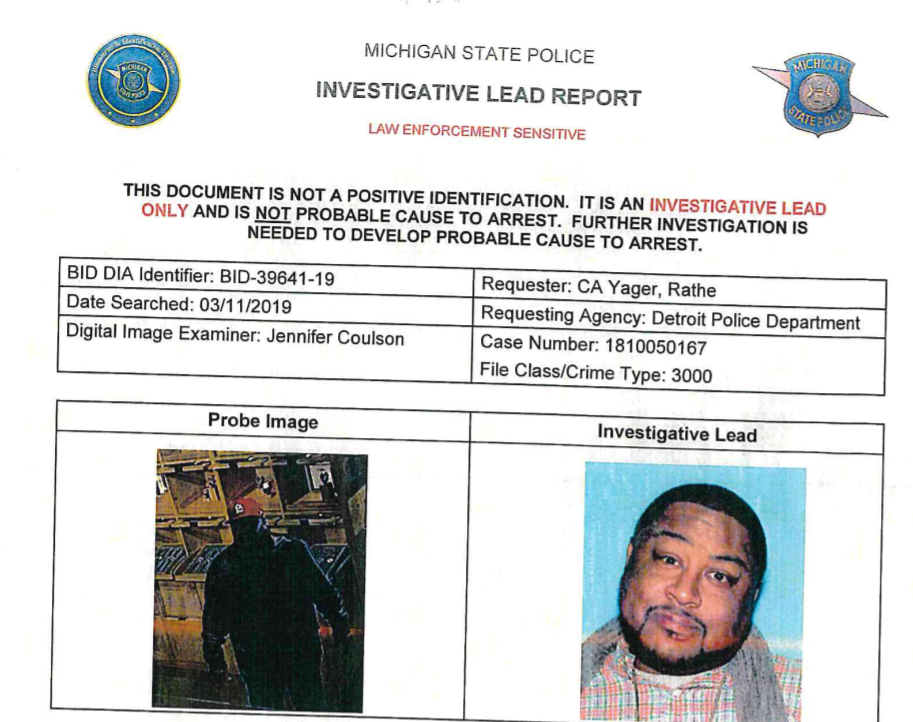

The wrongful arrest that triggered the lawsuit was not the first wrongful arrest made based on a facial recognition mismatch. It wasn't even the first made by the Detroit Police Department—who wrongly arrested Robert Julian-Borchak Williams in early 2019.

It is no coincidence that the two wrongful arrests made after bad facial recognition matches were of Black men, who had evidence of their innocence. One had an alibi, and the other had tattoos to prove that they were not the suspect in the surveillance camera footage.

The first arrest happened after the innocent man provided an alibi and pointed out that the surveillance video suspect looked nothing like him other than being Black. This led one of the detective's to remark to his partner that "I guess the computer got it wrong." Unable to overcome that presumption, he spent 30 hours in custody before he made bail.

The arrest of Michael Oliver was sloppy by any measure of the word and is currently the subject of a $12 million lawsuit. It is particularly egregious because the department apparently learned nothing from its first mistaken arrest based on facial recognition technology. The suspect they were looking for was heavier and had no visible tattoos, while the man they arrested days after had many visible, faded tattoos. Even this was not enough to stop his arrest or prosecution.

In these two cases, police were too dependent on a flawed technology. Both men allege police built their investigations around proving the computer matches correct, instead of looking for evidence that would have proved the matches were wrong. Luckily for these two men, they had evidence of their innocence. Although they were not too lucky, as they spent days in jail, and Oliver lost his job and had his car impounded. Williams was arrested at his home at gunpoint in front of his distraught wife and young children. He was so humiliated by what happened he never told his mother of the incident or truthfully explained his two-day absence to his colleagues.

STATE, LOCAL, FEDERAL, AND CORPORATE BANS

California was the third state, after Oregon and New Hampshire, to pass a limited ban (A.B. 1215) on facial recognition, with the ban only covering data from police body cameras and other devices carried by police.

San Francisco was the first U.S. city to ban facial recognition in May 2019. Their Stop Secret Surveillance Ordinance goes far beyond facial recognition and creates rules regarding all government surveillance stating "it is essential to have an informed public debate as early as possible about decisions related to surveillance technology." Consequently, the ordinance requires a public debate, the involvement of elected officials, and the adoption of policies that establish oversight rules, use parameters, and include protections for civil rights and liberties for any surveillance technology that is adopted in the future.

San Francisco was soon followed by Boston-suburb Somerville, MA, which banned facial recognition software on cameras that record public spaces. Six other Massachusetts communities would eventually adopt bans as well.

Oakland acted in July 2019. Their next-door neighbor Berkeley passed a similar ordinance soon after, making it the fourth ban in the nation.

Santa Cruz banned any facial recognition use by police in June (passed as part of the nation's first ban on predictive policing), with any future use requiring new legislation and evidence that proves the technology will not perpetuate bias.

Boston passed a broad ban on police use of technology in June as well—making it the second-largest city with a ban in effect.

Portland, Maine passed a ban on any city employees using facial recognition in August.

Portland, Oregon, not to be outdone, passed the toughest facial recognition ban in the nation this September—banning all governmental and private use of facial recognition.

Jacksonville, Mississippi passed a ban on police use of facial recognition in August—the first in the South.

Massachusetts is on its way to becoming the first state to have a comprehensive ban on facial recognition—unless New Hampshire or Oregon beats them to it.

Mohammad Tajsar, of the ACLU, describes this as "a wave sweeping across the country" and says, "Long Beach and other cities in Southern California should join the party if they are serious about protecting civil rights."

WHAT UNREGULATED FACIAL RECOGNITION CAN BECOME

To see what unrestricted facial recognition use looks like, look to China. In China, facial recognition is used on all crimes, no matter how small. By using a combination of video analytics and facial recognition, the police can generate jaywalking tickets—like we get red-light tickets in the U.S. There are also digital displays on the street that show the images of these jaywalking scofflaws after they commit their crime, even children.

Chinese use of facial recognition doesn't stop at petty crime. To prevent toilet paper theft, some public toilet paper dispensers scan your face before dispensing your serving and then lock you out for 9 minutes. When combined with social credit scores, facial recognition technology can be used to lock you out of much of society.

WHAT LONG BEACH CAN DO ABOUT FACIAL RECOGNITION

The Long Beach City Council could pass a ban on police use of facial recognition technology, or at least a moratorium until the technology's bugs are worked out, and issues of racial and gender bias are addressed. CheckLBPD sees the wisdom in such a ban and agrees with the points made by the ACLU. We also recognize that such a policy would face an uphill battle in Long Beach given our politically powerful police union.

If the LBPD wanted a policy that offers ways to reduce mistakes, they could look to the new facial recognition policy adopted on Sept. 12 by the Detroit Police Department. The policy the Detroit PD's put in place after its original policy was proven ineffective requires multi-level peer review, sets oversight requirements, limits use to violent crime, bans use at protests and for immigration enforcement, and sets other rules for how the systems must be used—with violations of the policy considered "major misconduct" resulting in dismissal from the department.

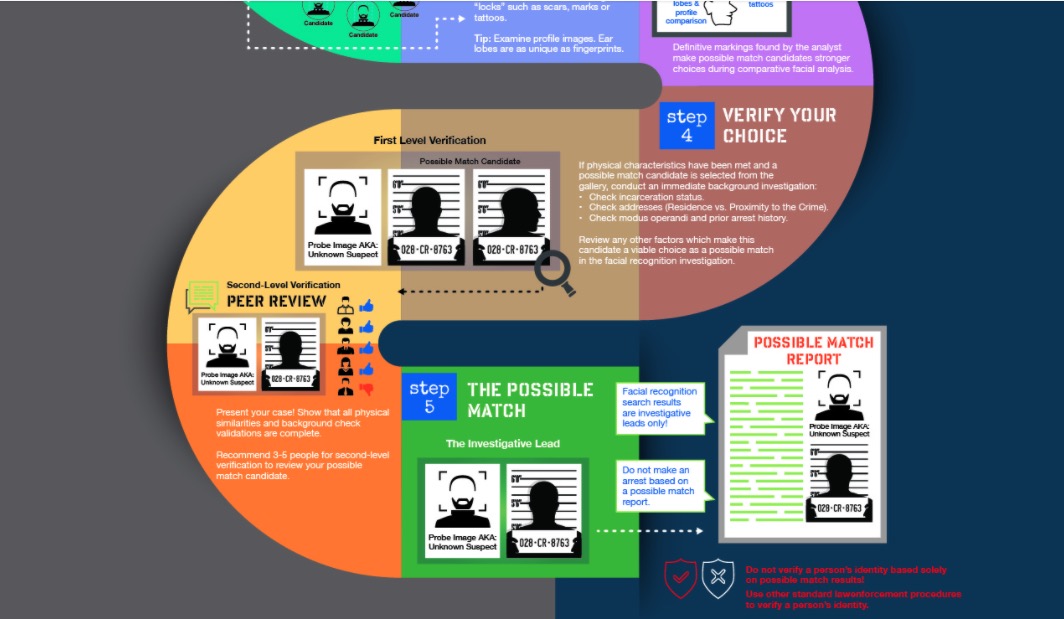

Given the technology’s short-comings and the risks inherent in police making contact with suspects, multi-level review and verification by specially-trained facial examiners should be a requirement before any contact is made with a suspect. The value of these two safeguards was mentioned in the Vigilant Solutions' training session for the LBPD. Vigilant Solutions' online training material recommends a second round of review using 3-5 reviewers, although it is unknown if this was a step ever taken by the LBPD.

A group no one will ever confuse with the ACLU also has issued guidance on facial recognition. The International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) issued a report by a team of 18 criminal justice experts and high-ranking police officers. This report came up with four recommendations, all of which would be changes to current LBPD transparency, practices, and policy.

The IACP recommendations are: "1. Fully Inform the Public, 2. Establish Use Parameters, 3. Publicize its Effectiveness, and 4. Create Best Practices and Policy."

Whatever Long Beach does, experts on both sides of the debate agree the decision-making process should be transparent and include public involvement. These technologies can and will transform society as we know it, so the people should have a voice in any decision made. The decision should not be made behind closed doors by the police in consultation with the companies that make the technology.

WHAT YOU CAN DO ABOUT FACIAL RECOGNITION

Lobbying local governments has been an effective way of getting legislation passed on facial recognition in cities across the nation this year. Hopefully, our elected representatives in Long Beach will address the issue—now that the LBPD’s use of facial recognition technology is public knowledge.

However, if you are not the type of person to wait for the government to act, you can opt-out of Clearview AI and remove your photos from their 3 billion photo database under the California Consumer Protection Act (CCPA). This process, and what others have discovered through it, will be discussed in an upcoming segment focused solely on Clearview AI.

Vigilant Solutions does not have the same interpretation of its responsibilities under the CCPA. I have tried to get copies of my automated license plate reader and any facial recognition data that may be in the Vigilant Solutions databases, but the company will not acknowledge that any data stored about my geolocation and stored under my license plate number is my personal data. Their argument seems to be based on the claim they have not linked the plate number to a name on their system, though that is both a legally and factually questionable argument.

Vigilant Solutions' argument regarding license plate data seems to overlook that the CCPA covers "information that identifies, relates to, describes, is reasonably capable of being associated with, or could reasonably be linked, directly or indirectly, with a particular consumer or household” and that the law has a clear definition for “deidentified” data they they seem to fall short of meeting. Their FaceSearch database contains names and other personal information, as seen in Vigilant Solutions' training material. So far, it appears Vigilant Solutions has not expanded beyond mugshots and crime stoppers photos, but even people charged or convicted of crimes have rights under the CCPA.

Perhaps these views on other people's data are why Vigilant Solutions is facing a class-action lawsuit in Illinois for violating the state's privacy laws by retaining the mugshots of wrongfully-arrested and exonerated people, even after their convictions were overturned and their records expunged.

Or if you are looking for a fashionable way to defeat facial recognition, there are options.

Anti-facial recognition hair and make-up styles created CV Dazzle styling.

Photograph: Adam Harvey, DIS Magazine

Have you been affected by facial recognition in Long Beach? Contact us to help us further report on this issue.

Questions, comments, or tips can be directed to Greg@CheckLBPD.org

This article was written by Greg Buhl, a Long Beach resident and attorney.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Feel free to distribute, remix, adapt, or build upon this work.