Citizen Police Complaint Commission Powerlessness and Secrecy Illuminated by the Death of George Floyd

In the past, when former Citizen Police Complaint Commission (CPCC) members wanted to speak publicly about the commission’s problems, they were reportedly told by the City Attorney that they could be charged with Brown Act violations for doing so—a threat they took seriously. But the body’s last regular meeting on June 11 went past midnight, as the commissioners spent more than three hours in open session, and eight hours total, airing out the problems with the CPCC. This was a radical departure from the first half of the year, when the open session portion of the commission’s meetings averaged 25 minutes, with some as short as ten minutes.

Instead, the first CPCC meeting since the killing of George Floyd stretched into the night and was full of productive discussions, contentious issues, and unanswered questions. The meeting went so long, it required a second special session two weeks later.

JUNE 11 MEETING

One of the most noteworthy exchanges involved the discussion of the CPCC’s subpoena power, a topic that was brought up repeatedly throughout the meeting. In 1990, Long Beach voters created the CPCC by amending the City Charter—a document that can best be described as our city’s Constitution, as there is no higher local law. The CPCC was ostensibly designed to investigate complaints lodged against Long Beach police officers. It was given the power to subpoena witnesses, swear them in under oath, and compel the production of documents.

The CPCC is made up of 11 members of the general public, with each councilmember appointing one commissioner and two serving as at-large commissioners. The commission is overseen by a Commission Manager housed in the City Manager’s Office, and employs two investigators who report to the manager. The CPCC meets monthly to hear cases in closed sessions and then makes recommendations to the City Manager, who makes the ultimate disciplinary decision against officers accused of misconduct.

Despite having the power, the CPCC has never once subpoenaed a witness in its 30-year history—a fact confirmed in the meeting by the Deputy City Manager Kevin Jackson.

Later, when commissioners expressed being in favor of finally exercising the body’s subpoena power, city staff were hesitant, bordering on pessimistic, about the idea.

PLEADING THE FIFTH?

Deputy City Attorney Sarah Green explained why there were difficulties in subpoenaing LBPD officers. The tentative answer given was that even if officers were compelled to appear before the CPCC, they “may not testify substantively … due to Fifth Amendment issue[s], or on the advice of counsel.” Green said that, like the commissioners, she was new to the commission and would need to “dig into that, but from what I understand there are complications.”

That was somehow the end of the discussion and not the beginning of a discussion on why an LBPD officer would ever need to assert their right against self-incrimination when discussing a misconduct allegation under oath before the CPCC. Police officers already enjoy qualified immunity, a cozy relationship with the District Attorney, a protective labor contract, and experienced legal representation courtesy of their union. Given that the CPCC hears cases in closed session, and that all commissioners are sworn to keep the closed sessions confidential, there is no more need for officers to plead the Fifth if questioned by the CPCC about a misconduct allegation than there is when they speak to LBPD investigators.

CPCC commissioners also discussed how they are now receiving body camera footage, and said that hearing from the officer in person would help put that footage into context. Also noteworthy, is that CPCC investigators get access to information that may later be redacted from the file given to the CPCC commissioner, but not even the CPCC investigators get access to the compelled statements officers make after an incident, as was explained by LBPD Commander Dina Zapalski at the meeting.

Another notable exchange surrounded a bizarre Catch-22 situation involving residents who want to make reports to the CPCC directly. Upon repeated questioning from Commissioner Porter Gilberg, city staff could not detail how someone could file an actionable complaint with the CPCC that did not result in the LBPD receiving the complainant’s identity. The problems exist because CPCC investigators share information with LBPD Internal Affairs, which conducts its own concurrent investigations.

The Commission Manager, Patrick Weithers, stated that the CPCC does receive anonymous complaints. That claim was met with an immediate question from Gilberg about whether any of those anonymous complaints have ever been sent to closed sessions for a hearing before the commission. Again, city staff was unable to provide an answer to the question. Weithers offered to look into it and send the commissioners the answer later on. Gilberg asked if he could have his answer at the July meeting open session instead, to which Weithers agreed.

NO FURTHER ACTION

Of the seven reasons for closing an allegation, No Further Action (NFA) is the most common finding made by the commission going back to 2002. The share of allegations closed with an NFA finding has routinely been over 70%, peaking at 88.5% in 2006, with a second peak of 86% in 2012. Reasons for closing an allegation with an NFA range from CPCC investigators being unable to locate a witness, a witness being uncooperative, or if a complaint is withdrawn. Sometimes it’s simply a staff recommendation.

But beyond this, the commissioners are not given further details about why a case is marked NFA, even as they’ve been approving all NFAs as part of their meeting’s consent calendar.

Commissioner Justin Morgan said many of the CPCC’s decision-making processes felt “like walking in the dark.”

The latest annual report available shows that in 2014, 232 out of 461 allegations were NFAs. The same annual report—which boldly covers two years in defiance of both the word “annual” and CPCC bylaws—shows that in 2015, only 282 allegations out of 742 were able to be heard by the CPCC during their monthly meetings. Of those, 94 resulted in NFAs.

Weithers said during the meeting that it can take as little as a complaining witness not returning a voicemail for the case to be marked NFA due to lack of cooperation. CPCC staff can also decide to mark cases NFA based on their personal reading of the facts. All in all, the current system requires commissioners to have blind faith in CPCC investigators—who report to the City Manager by proxy of the Commission Manager—when rubber-stamping NFAs. This raises serious questions about independence, especially in light of previous whistleblower allegations from a past CPCC investigator, which we’ll get to in a minute.

Weithers went on to explain that he had heard previous criticisms of the NFA process and acknowledged that improvements to the system were needed. In the meantime, as a stop-gap measure, NFA cases are being moved to closed sessions to allow the commissioners to receive more detailed information than the vague explanations they could receive in a public session. The trade-off being that, for now, the public will not even get the two or three words of explanation we had been receiving—such as lack of evidence, witness unavailable, or staff recommendation. Weithers estimated that there would be about 20 NFA cases per month to add to the closed session calendar.

But with cases already bottlenecking and timing out, it’s questionable if the CPCC—whose commissioners have only just been approved by City Council to receive a stipend for each meeting—would even be able to get through another stack of cases in their once-a-month summits.

Looking at the numbers for 2014 and 2015, only a small percentage of cases were heard by the CPCC commissioners. In 2014, the CPCC held closed session hearings on allegations from 30 cases out of the 214 it could have heard. In 2015, only 62 out of 336 cases brought in 2015 or leftover from 2014 got a hearing. When the CPCC does hear a case, it has often been nine months or longer from when the complaint was filed. And even if the commission does sustain an allegation of officer misconduct, their finding is only a recommendation.

CPCC RECOMMENDATIONS SHOT DOWN

The City Manager, a position currently held by Tom Modica, is the ultimate authority on the allegations the CPCC reviews. He can ignore the CPCC recommendations and rule based on his own opinion of the case. In an interview last year, former City Manager Pat West said the CPCC is overruled about 5% of the time. While that seems like a low rate, a review of all four annual reports filed over the last decade shows that 5% is approximately how often the CPCC sustains allegations of wrongdoing.

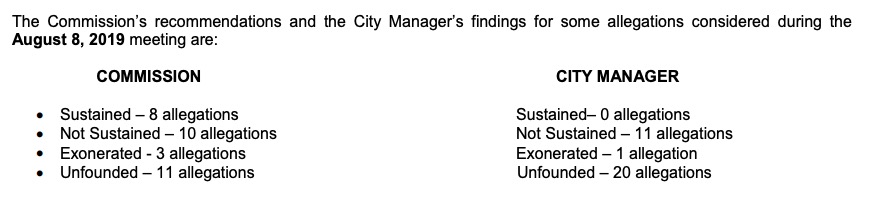

Looking at the City Manager Reports to the CPCC shows how often the City Manager ignores CPCC recommendations and how little information regarding why this is done is made public. This is evident in the City Manager’s Report on the August 2019 CPCC meeting, as well as the other seven reports filed over the last thirteen months. The report filed last August shows all officer misconduct allegations sustained by the CPCC were ignored. What’s more, commissioners were not told why or how their decisions are changed, being left to guess based on totals reported by the City Manager.

August 2019 City Manager CPCC Report.

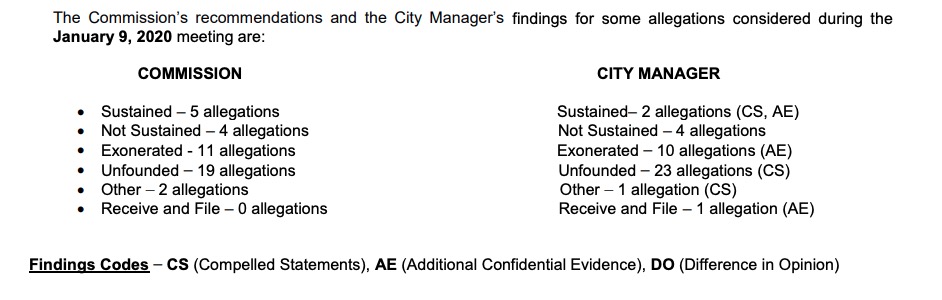

In a slight improvement, as of June 2020 commissioners are now given vague explanations for why the vast majority of their recommendations are overturned. From the City Manager’s report to the CPCC submitted prior to the June 11 meeting:

January 2020 City Manger CPCC Report.

The August 2019 City Manager’s Report overturning all CPCC recommendations is not an anomaly. A review of the City Manager Reports to the CPCC going back to June 2019 illustrates how often this is done. One can see that the CPCC recommendations are rarely followed, with only 4 of 31 sustained allegation recommendations being followed by the City Manager since the June 2019 report—which covers March 2019 CPCC decisions.

| Date of Report | CPCC Sustained Recommendations | City Manager’s Sustained Decisions |

| June 2020 | 5 | 2 |

| March 2020 | 3 | 1 |

| Jan. 2020 | 5 | 0 |

| Oct. 2020 | 8 | 0 |

| Sept. 2019 | 8 | 0 |

| Aug. 2019 | 1 | 0 |

| June 2019 | 1 | 1 |

| TOTAL | 31 | 4 |

At June 11 meeting, the commissioners repeatedly asked about the process by which CPCC recommendations are considered and overruled. Weithers confirmed that the City Manager can and does overrule the CPCC even when he has no additional evidence. He went on to simply say, “That’s how it works.”

Multiple commissioners had thoughts on this, with the consensus being that they put a lot of time into their decisions and would appreciate more transparency regarding when and why the City Manager overrules them.

LBPD POWER VERSUS CPCC INDEPENDENCE

The lack of a mechanism for the CPCC to accept and investigate anonymous complaints is reminiscent of a policy recently enshrined in the Long Beach Police Officer Association’s most recent agreement with the city. That binding document requires the City to give LBPD officers the name of anyone who requests their disciplinary file through a California Public Records Act request. The officer not only gets the requestor’s identity, but even gets the responsive documents five days before the requestor receives the documents.

Additionally, officers enjoy the protection of having their disciplinary files routinely destroyed by the LBPD, so the public can not request them. The LBPD routinely purges all disciplinary files over five years old, though after recent public protests, they have put that plan on hold for at least a year.

The Long Beach Police Officers Association (LBPOA) is active in local political campaigns, and has been an effective advocate for the LBPD since its founding in 1940. Illustrating the LBPOA’s political spending, Mayor Robert Garcia’s campaign and ballot measure committees have taken in over $500,000 from the LBPOA since 2015. But the LBPOA also makes independent expenditures in favor of Garcia and other candidates.

Discovering how much money Garcia has taken over his entire political career is impossible from the documents available to the public, which do not include his older city council campaigns. Like the disciplinary files of police officers, records of local politician’s campaign contributions can be purged every seven years under the California Fair Political Practices Commission rules.

While there is no way of knowing with certainty the motivation behind the LBPOA’s political spending, if the city’s budget priorities and agreements with the LBPOA are any indication, it’s clear that the LBPD wields significant negotiation power within City Hall.

In 2019, Long Beach appropriated 44% and spent 48% of its budget on the LBPD, and that is before adding in the millions spent every year on police-related misconduct lawsuits. The city has been paying out an average of over $20,000 per day for police misconduct the last five years, without counting the massive legal fees the city pays to outside counsel. Long Beach spends a greater percentage of its budget on police than Atlanta, Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York City. When overtime is considered, Long Beach Police officers are among the highest compensated city employees with 300 officers whose total pay and benefits are over $200,000 per year. Pay raises are guaranteed by the same LBPOA-negotiated contract that gives LBPD officers notice of when and by whom their disciplinary file is requested.

There were several times in the meeting where commissioners expressed a desire for more independence from the LBPD. Currently, the training of CPCC commissioners is conducted by the LBPD, not by the CPCC staff or outgoing commissioners, who could pass along what they’ve learned over their two-year terms. Part of the onboarding process set out in the bylaws requires CPCC commissioners to go on a ride-along with the LBPD. Not mentioned in the bylaws is that to go on a ride-along, one must first pass a Livescan fingerprinting conducted by the LBPD.

Gilberg, who last month called the CPCC a “farce,” mentioned that he had asked at the time of his fingerprinting if the results were used to determine eligibility to serve on the CPCC. He wanted to know if someone’s Livescan results caused the LBPD to refuse to allow them on a ride-along, was that person then ineligible to serve on the CPCC. Gilberg said his inquiry was never answered when he asked last year, though an answer has been promised at the next meeting.

In his closing remarks, CPCC Chair Desmond Fletcher acknowledged the difficulty of achieving meaningful change but said the moment is so critical it motivated him to go to a protest for the first time in 20 years. To local leaders and police, he stressed that cooperation with residents is essential and that now “is not a time to get entrenched in your power."

FORMER CPCC INVESTIGATOR’S WHISTLEBLOWER COMPLAINT

Over two weeks later, at a special meeting held on June 26, commissioners debated about how best to question former CPCC investigator and whistleblower Thomas Gonzales. Some of the complaints made by Gonzales, who worked for the commission between 1999 and 2006, track with the concerns commissioners are now raising over a decade later.

His attorney Kimberly Lind had previously submitted a public comment that went unacknowledged during the June 11 meeting, likely because, according to Weithers, public comments had been emailed to commissioners just before they met.

“To make the CPCC legitimately independent and viable,” Lind wrote, “The investigators require protection from the influence of the POA, appointed commissioners should not have ties to the police force they review, utilized/enforceable subpoena power and real disciplinary authority apart from the City Manager’s approval/veto.”

Gonzales won a $700,000 wrongful termination lawsuit against the city after being fired for shining a light on some of the commissions’ inadequacies. The city shelled out another $300,000 in legal fees for his defense.

He alleged that when a fellow investigator, and former police officer, was promoted to executive director (a position the CPCC no longer fills), the commission became a hostile place for him to work. Gonzales detailed how the new director took anti-Hispanic actions—including removing the Spanish language portion of the CPCC’s voicemail greeting. The new director also took a series of pro-police actions—including prominently displaying LBPD photos and memorabilia in the office, holding closed-door meetings with LBPD officers, and rewriting Gonzales’s reports to soften criticism of the LBPD. In his lawsuit and publicly reported comments, Gonzales also made specific allegations about the NFA designation being used to hide misconduct from the CPCC and the public.

In one interview, he said, “back then [2006] they not only stopped me from interviewing the officers, they even tried to stop me from interviewing the citizen complainants, but I did it anyway. Many times I found that the investigators attributed statements to the complainants that they never said. And it was always in support [of] whatever new cover-up the LBPD was cooking up.”

He also alleged a series of problems with the CPCC Annual Reports, including that Councilmember Al Austin (CD-8) improperly signed the 2002 Annual Report even though the first of his two CPCC commissioner terms did not start until 2003; that the 2003, 2004, and 2005 reports are cut-and-paste jobs; and that the 2002 and 2007 reports intentionally misstate how many actual investigations were conducted by counting uninvestigated NFAs.

Annual reports are supposed to be more than just raw numbers, and besides presenting data they can be a source of policy recommendations. The last annual report issued by the CPCC was published in 2015. The report recommended “look[ing] internally and externally to ensure that [the CPCC] is complying with City Charter requirements and to review its authority and opportunities to serve and engage the community,” after which time the CPCC stopped issuing annual reports, despite the body’s bylaws stating that a report should be filed each year.

Since so much of the work the CPCC does is conducted in closed sessions and the case reports are not public record, the annual reports are one of the best ways the public has to see what the CPCC does for Long Beach. The lack of annual reports deprives the citizens of Long Beach of a chance to see statistical data on police misconduct allegations that could lead to increased accountability and improvements in police training and procedure.

Since this article was initially published, the CPCC has issued the Annual Reports it had been skipping for the last five years. Unfortunately, those reports have many of the problems found in past annual reports, and the data contained in them does little to increase transparency or accountability.

The city also completed its Framework on Reconciliation, in which the CPCC was a frequent topic of discussion. While no reform has yet taken place in 2020, there has at least been an increase in funding. The city plans to use the increased funding for 2021 to commission a $150,000 study on CPCC reforms and innovations.

In the near future, CheckLBPD will review all the new CPCC annual reports to look for trends and additional areas of reform suggested by the data (or lack of data). We also eagerly await the city’s $150,000 report on CPCC reforms and innovations.

This article was originally published by FORTHE Media as “Like Walking in the Dark”: Citizen Police Complaint Commissioners Push Back Against Secrecy, Powerlessness”

Questions, comments, or tips can be directed to Greg@CheckLBPD.org (encrypted on our end with protonmail)