Preview: CheckLBPD’s In-Progress TigerText Independent Investigation

Other than the Long Beach Police Department, the Georgia Department of Corrections was the only law enforcement-type agency to ever use TigerText. Prison employees in Georgia used it briefly in 2013, before the department's lawyers determined its use violated the state's record laws and could lead to violations of discovery rules in criminal or civil trials.

In Long Beach, the police used TigerText for almost four years, sending 261,799 messages, with no such determination ever being made. It never occurred to the LBPD, or the city attorney, the city prosecutor, the city council, the Citizen Police Complaint Commission, or the L.A. District Attorney. In other cities, each of these offices would have some role in oversight, but in Long Beach they failed to act.

As you can learn on this site, the TigerText scandal was just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the LBPD's unregulated use of technology, whose use has real implications for the civil rights and liberties of individuals and the rights of opposing parties in civil and criminal trials.

UNCOVERING TIGERTEXT

It wasn't the City Attorney, the City Prosecutor, the Citizen Police Complaint Commission, or the L.A. District Attorney that uncovered the TigerText scandal. It was Stephen Downing of the Beachcomber through relationships with multiple confidential sources inside the LBPD. These sources trusted Mr. Downing, both as an uncompromising reporter who would never reveal the identity of a whistleblower, and as a retired LAPD Deputy Chief who would treat the issue with the seriousness it deserves.

Mr. Downing's requests for documents were stonewalled by the LBPD, leading him to consult with the ACLU—who filed their own Public Records Act (PRA) requests. When the ACLU made its request, the LBPD produced the documents regarding Tigertext, which it had denied Mr. Downing.

By this time, Mr. Downing was working with Jeremy Young, a reporter for Al Jazeera, on a variety of investigative inquiries into the LBPD's organizational culture. To test the department's integrity, Mr. Downing asked Young to file his own PRA requests that would mirror a Beachcomber request. As he expected, Mr. Downing's request was denied yet again, while Al Jazeera was given the same documents produced to the ACLU.

The Beachcomber and Al Jazeera would both publish their articles on the scandal on Sept. 18, 2018; the last LBPD TigerText message would be sent at 6:41 PM that day.

The traffic on TigerText during the last five months of usage may be particularly revealing. The LBPD knew Mr. Downing was aware of TigerText when he started filing PRA requests on the subject earlier in the year—so it is conceivable the LBPD was using TigerText to cover-up their use of TigerText. Future investigation will look at the timing of these requests and the Tigertext message traffic that they may have inspired.

OFFICIAL INVESTIGATION INTO TIGERTEXT

After the use of the program was uncovered, the city commissioned an "independent" investigation from Gary Schons of the law firm Best, Best, and Krieger (BB&K) for $18,154.36. You'll have to read to the bottom of this article to see why I put "independent" in quotes. It's a good reason or more like close to a million good reasons.

The BB&K report was lacking in many ways, and CheckLBPD agrees whole-heartedly with Mr. Downing, who calls BB&K report a cover-up and a whitewash. The BB&K report became the definitive investigation into TigerText, with the city attorney and city prosecutor deferring to it, while an investigation by the L.A. District Attorney's Pubic Integrity office went nowhere.

The BB&K report accepts the LBPD's explanation that TigerText was only used to convey "call outs, operational planning, needs and communication, and the status or results of operations in nearly real time." Schons found "TigerConnect app is not used for 'note taking' or as a replacement for any aspect of PD official report writing or evidence retention."

In the report, Schons finds that there is no evidence to support claims of improper use. If you believe the BB&K report, the LBPD used Tigertext for four years without creating a single issue related to discovery obligations in civil or criminal trials and without violating any public records laws. He bases this on the absence of saved messages for him to review and legally questionable analogies comparing the use of TigerText to phone calls and handwritten notes.

For LBPD investigative units, the BB&K report found that "such secure messaging technology was vital…because of the sensitive information often included in these instant messages which could relate to violent crimes, security and emergency matters, crime victims, confidential sources of information, operational plans, and personnel matters, among others."

While this is a legitimate point, CheckLBPD finds it odd that the system was not used by the group that would handle the most sensitive victim information, the sex crimes unit. Most sex crimes investigators do not seem to have been issued accounts, and those that were never used TigerText beyond sending and receiving the introductory messages required to make an account.

A core conclusion of the report is that "the speculation offered by the ACLU and a Deputy Public Defender that the use of the TigerConnect app by the PD might have violated various laws and court decisions is simply sensational conjecture and, as a matter of law, inaccurate."

Mr. Downing, at the time the BB&K “investigation” was received, reviewed, and filed by the Long Beach City Council’s Public Safety Committee, chaired by Council Member Suzie Price (also a senior prosecutor in Orange Country, as city council member is a part-time position in Long Beach), pointed out the major flaw in the BB&K investigation. That flaw was that the BB&K attorney never bothered to interview any of the investigators assigned use of the TigerText app or the Investigations’ Lieutenant, Lloyd Cox, who originally recommended its use to the department and hosted multiple training sessions on its use. An officer Mr. Downing interviewed recounted that “Lloyd Cox, told us in a weekly homicide unit meeting in the 5th-floor conference room to use it [TigerText app] to discuss information that should stay within the unit and not be discoverable.”

CheckLBPD's review of the TigerText metadata shows that the "sensational conjecture" has as much, if not more, a basis in reality than the claims made in the BB&K report. We consider the message traffic patterns to be extremely telling. The lack of evidence found by the BB&K report is not an indication of the LBPD's innocence; it is an indication of a failure to investigate thoroughly.

What follows is a preliminary sampling of some of our findings, looking at just a few specific incidents that occurred in Long Beach and the traces they left in the TigerText metadata.

OVERVIEW OF LBPD TIGERTEXT USE

A look at the raw metadata shows that TigerText was mainly utilized by the top leaders of the LBPD—with relatively little use by investigators. The top ten users accounted for over half the messages sent on the system, with the vast majority of messages being individual back-and-forths between the department's top brass and public information officers.

Below are the 21 most active TigerText users, out of a total of 145 LBPD accounts, and their share of the 261,799 messages sent.

1. David Hendricks - 23,928

2. Megan Zabel - 20,334

3. Wally Hebeish - 16,761

4. Joel Cook - 16,112

5. Robert Smith - 14,641

6. Lloyd Cox - 14,605

7. Robert Woods - 11,201

8. Benjamin Vargas - 10,984

9. Richard Conant - 10,231

10. Jeffrey Berkenkamp - 7,406

11. Michael Beckman - 6,602

12. Steve Lauricella - 6,231

13. Phillip Cloughesy - 5,928

14. Sean Irving - 5,681

15. Anthony Lopez - 4,987

16. Gaynor Joseph - 4,696

17. Erik Herzog - 4,645

18. William Lebaron - 3,957

19. Peter Lackovic - 3,915

20. Michael Pennino - 3,896

21. Robert Luna - 3,876

The record for most messages sent in a day goes to then-Deputy Chief of Investigations David Hendricks with 446 messages.

He routinely sent hundreds of messages a day. Most of his traffic was messages to Megan Zabel while she was the Police Information Officer (before being promoted). He routinely sent her hundreds of messages a day, including the person to person daily record of 417 messages.

Most of Hendrick's auto-delete settings on his messages were set to less than a day, with some messages set to delete after just five minutes.

Users could select different retention periods for different messages. Five days appears to be the default. The metadata shows messages staying on the systems for as long as 30 days.

Hendricks, like other high ranking Long Beach officers, later became chief of police in a smaller city.

Hendricks' tenure as Fullerton PD Chief was short-lived. He was arrested while off-duty after he and another officer drunkenly assaulted two paramedics at a Lady Antebellum concert. He was charged with two counts of battery on emergency workers and one count of resisting arrest. He would later plead guilty to disturbing the peace and pay a $500 fine—a deal that let him avoid any jail time.

POTENTIALLY RECOVERABLE MESSAGES

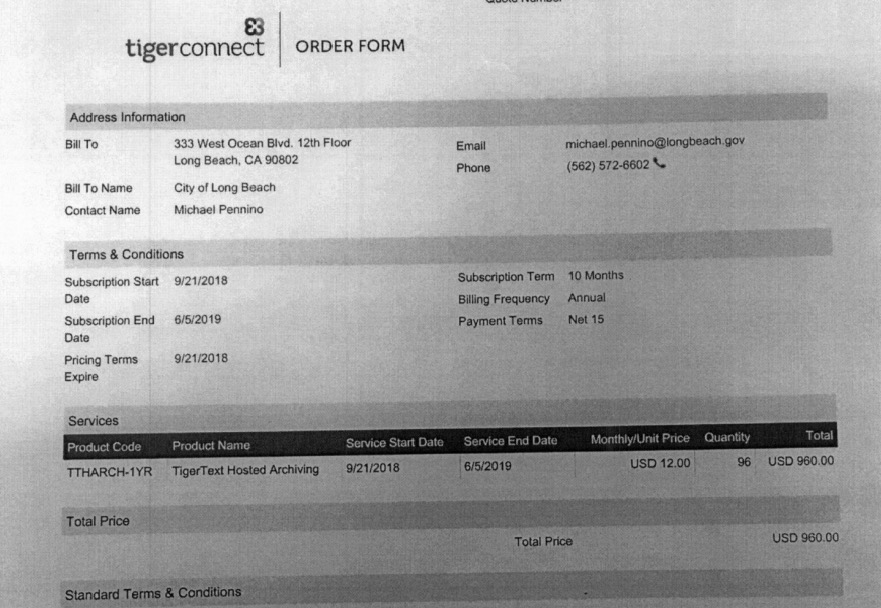

The BB&K report mentions that the LBPD had the option of having TigerText archive their messages for only $960 per year, a relatively small additional cost for a program that was already $9,888 per year.

The BB&K report glosses over this topic, with footnote 11 at the end of the report being where the reader learned how relatively inexpensive it would have been for the LBPD to get the secure messaging it said was its goal—while also retaining messages to comply with public records laws and the Brady requirement to turn over exculpatory evidence to the defense in criminal trials.

The obvious response to this is that the LBPD would have security concerns about messages being stored on a private server. For several reasons we describe below, we think it is possible some messages were stored on TigerText servers regardless of whether the LBPD paid the $960 annual additional hosting fee.

Schons' report mentions how TigerText's annual fee of $9,888 was paid by the LBPD, with the last annual payment in that amount being in 2018. The last $9,888 annual fee payment was made in July 2019, with the program being canceled that September.

Not mentioned in the BB&K report is that the LBPD made payments to TigerText on October 11, 2018 and November 15, 2018, in the amounts of $768 and $2,500. These charges were made after BB&K was hired—but before the report was issued at the end of November. CheckLBPD discovered these payments in LBPD vendor records being reviewed for another CheckLBPD project, the Surveillance Architecture of Long Beach.

TigerText invoices and purchase orders from late 2019 (posted here along with other documents produced by the LBPD in response to PRA requests) show that on September 21, 2018, the department ordered ten months of "Hosted TigerText Archiving" for $960. This was just three days after the TigerText scandal was publicly reported. They would later pay a second invoice for $2,500, also for "Hosted TigerText Archiving" through September 2019.

The LBPD contact is listed Lt. Michael Pennino (promoted to Commander in 2019), and the invoices were signed off on by Administrative Bureau Chief Jason Campbell. The LBPD Records Department is listed as the recipient.

It is currently unknown what data the department paid $3,500 to archive. As noted above, the yearly fee for archiving was only $960 per year, and the department had declined to pay that archiving fee for the almost four years it used the system.

Perhaps coincidentally, $3,500 is about what the cost of archiving all Tigertext messages would have been over the lifetime of the program.

The situation grows even more suspicious. In the BB&K report, Schons writes that a "message cannot then be forwarded or stored unless TigerConnect has been tasked with archiving messages." Schons also wrote that the LBPD was not paying the extra fee for archiving. A review of the Tigertext manual shows that Schon was correct about archiving being necessary to forward a message.

However, the department was able to forward messages (823 messages that were forwarded on the system), as well as recall messages and send attachments. That seems to indicate that TigerText was saving messages. The fact the LBPD later paid for a year of hosted archiving (after they had stopped using the program) strongly indicates something was stored on the Tigertext servers.

Since the metadata could be easily downloaded and saved (all the metadata files together are under 25MB total, small enough to be emailed), it would be preposterous to pay $3,500 to have TigerText host 25 MB of metadata for a year. Additionally, the metadata would have been downloaded and made available to Schons, so there would be no reason to pay to just archive the metadata. There must be another explanation. Unfortunately, the issue was never explored.

If it was not all messages that were archived, CheckLBPD has identified some categories of messages that might have existed on TigerText servers and been archived.

For one, when archiving was purchased on September 21, 2018 (three days after the program was stopped and on the very day the city declared it was starting its "independent outside review"), there would have been a significant number of messages with unexpired message lifetimes. Many messages had their lifetimes set to 30 days, and many messages with the default five day lifetime would have still existed. A review of these messages was never pursued.

Instead, the only TigerText messages ever seen were the handful of messages Chief Luna took as screenshots on his phone and made available to Schons. These messages make up Appendix A of the BB&K report. A review of the metadata shows these messages were not the last messages (most recent) sent or received by Luna's account, but instead messages that were cherry-picked from a larger set of messages that would have been available.

These handpicked messages, selected by the Chief of Police personally, are then used to support the claim that there were no improper messages sent. A proper review would have had the department save and produce all available, undeleted messages when the review was announced three days after the TigerText review was announced on Sept. 21, 2018 (with BB&K hired within a week). Instead, the only messages ever reviewed were those selected by Chief Luna.

These Luna messages are how CheckLBPD determined that the metadata was saved in Greenwich Mean Time, not local Long Beach time. This is a relevant fact when you use the metadata to look into specific incidents, as we will do for the three incidents below.

Also unexplored are whether the 1,665 attachments that were sent using TigerText were archived in any way—as well as what sort of attachments were being sent and if they may have been items that should have been retained as part of a case file.

The LBPD paid $3,500 for ten months of archiving. What was archived and why it was never turned over is a mystery. A mystery that may be too late to solve—that is without cooperation and transparency from the LBPD.

THREE SCANDALS REFLECTED IN THE TIGERTEXT METADATA

In Part I of his two-part article dissecting the Best, Best, Krieger "Independent" Report, Stephen Downing makes a connection between previous PRA requests for LBPD communications on sensitive subjects that have come up empty and the use of TigerText.

When submitting requests under the California Public Records Act for text messages and communications "related to LBPD incidents involving controversial shootings, excessive use of force, misconduct and the cover-up surrounding the DUI/Domestic violence scandal involving 2nd District Councilmember Jeannine Pearce," Mr. Downing would always get the response no responsive documents exist.

At the time, Downing was suspicious he was not being told the whole truth but was unaware that it was the department's use of a disappearing messaging app that was inhibiting his requests.

In Schons' report, he uncritically accepts the department's claims about how they used TigerText. In his telling, the department was not using their disappearing text messaging app to have off the record conversations related to shooting review boards, departmental misconduct cover-ups, or to plan the department's response to multiple DUI scandals.

Schon's had many options for investigating that sort of usage. He could have made more of an effort to recover archived messages, he could have conducted an analysis of use based on metadata, or he could have interviewed more of the officers who were the end users of TigerText—ideally after examining their metadata so he could ask informed questions while having some sense of whether he was being told the truth.

Instead of pursuing any of these investigative avenues, Schons took the statements from LBPD leaders as the truth—and then wrote a report to support that version of events.

CheckLBPD does not have the investigative mandate that would allow for it to interview LBPD officers about the program, and any archived messages on TigerText servers are likely long gone. What that does leave us with is the TigerText metadata.

You can find the TigerText metadata on a webpage the City created to host the independent report and the documents that were reviewed for the report (though the collections are not complete, as the annotated timeline created by the department is missing). There you can find the completed ACLU and Al Jazeera PRA requests—though not the Beachcomber PRAs that did not receive accurate responses.

As a side note, we also find it a shortcoming of the report that the series of untruthful Public Records Act responses made to Stephen Downing was not investigated as part of the BB&K report. As you will see, if you read CheckLBPD's investigation into LBPD use of facial recognition, the LBPD has a history of making inaccurate responses to PRA requests on sensitive subjects.

The city produced the metadata as five large excel files, with inconsistently formatted names and the time set to Greenwich Mean Time. As is, these files are unusable. Even combined and formatted, they make a 261,799-row spreadsheet that is not exactly user-friendly.

CheckLBPD took things one step further and had a Google Data Studio dashboard created to make the process of analyzing the metadata possible. This important step allows for one to actually check whether the LBPD's characterization of their use of Tigertext was correct, something we consider essential to a proper investigation of the LBPD's use of the program.

You can access the metadata dashboard on the CheckLBPD website or through a Google Data Studio dashboard.

CheckLBPD's investigation is on-going (help is welcome), though we have made some preliminary findings that suggest further investigation is warranted.

CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JEANINE PEARCE'S DUI

One of the first things we looked at was Stephen Downing's suspicion that TigerText would have been used by top-LBPD brass to plan their response to the Jeanine Pearce incident. At the time of the incident, many were concerned that the LBPD showed preferential treatment.

According to an LBPD statement, Chief Luna "subsequently initiated an Internal Affairs investigation to address those concerns." The investigation included 22 separate interviews with LBPD officers, CHP officers, and civilian witnesses. Investigators also reviewed documents, reports, computer data, recordings, and other relevant data—spending 300 hours on the investigation before presenting their findings to Chief Luna.

The LBPD would eventually submit their findings to the Los Angeles County District Attorney's Office on June 29, 2017, for filing consideration. As is the norm when it comes to LBPD misconduct, the District Attorney's Office declined to prosecute. An L.A. District Attorney Public Integrity Division's investigation appears to have gone nowhere.

CheckLBPD thinks the departmental response was particularly worthy of investigation.

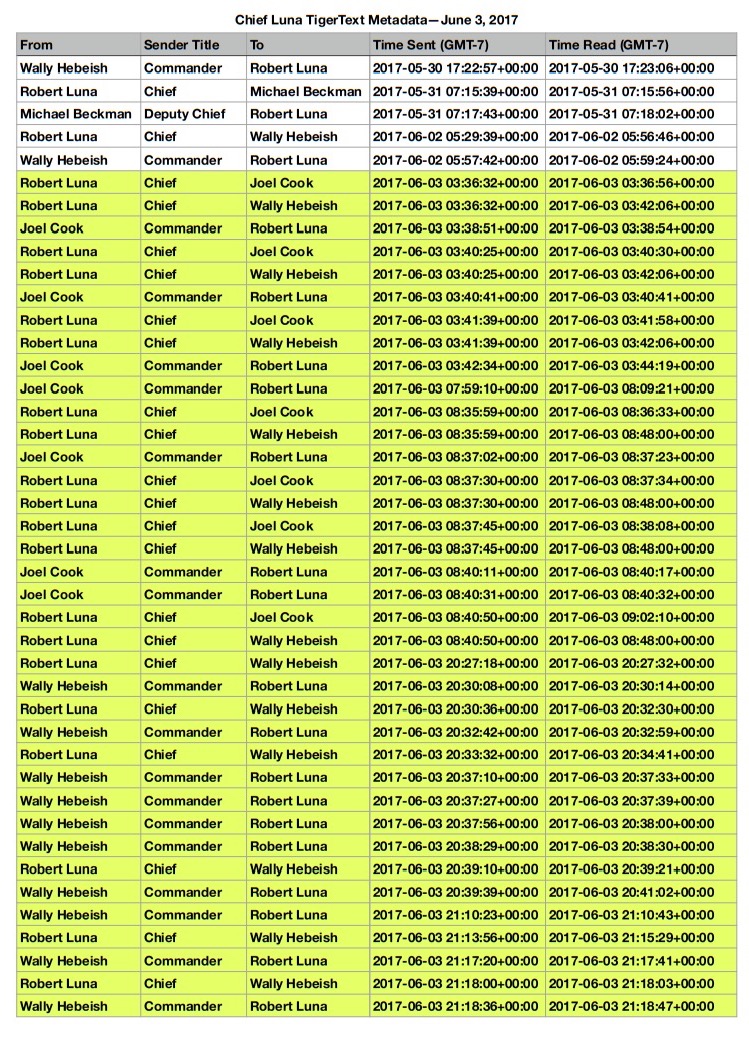

An analysis of the metadata shows that Chief Robert Luna was on TigerText exchanging messages with Commander Joel Cook and then-Commander Wally Hebeish within one hour of the June 3, 2017, 2:40 AM call for assistance from the California Highway Patrol about a possible drunk driving incident on the shoulder of the 710 Freeway.

Hebeish is now the Assistant Chief of Police and head of LBPD's new "Office of Constitutional Policing," which was formed as "a part of the Police Department's commitment to the City of Long Beach's framework for reconciliation."

On average, Chief Luna's Tigertext traffic was 5.5 messages sent or received per day. On June 3rd, Luna exchanged 37 messages with Hebeish and Cook. You can explore who sent who messages on which days using the Data Studio dashboard CheckLBPD has created. However, to dig deeper into the exact time of the messages, you need to use the spreadsheet of the combined years of reformatted TigerText metadata CheckLBPD has created.

Below is the series of messages exchanged by Chief Luna on June 3, 2017, converted from the metadata's Greenwich Mean Time numbers. Chief Luna's messages alone are telling, and they are just a drop in the bucket compared to the spike in overall TigerText usage triggered by the Pearce incident.

LBPD DETECTIVE TODD JOHNSON'S "ALLEGED" DUI

Todd Johnson was a notorious LBPD Detective well before the night of December 27, 2017, when he rear-ended another car—while driving an LBPD unmarked vehicle and smelling of alcohol. You will have to take the word of the man he crashed into that Johnson had been drinking because once the LBPD arrived on the scene, they made sure that Detective Johnson avoided the breathalyzer exam that would have been standard for a civilian who reared-ended another car while smelling of alcohol.

In fact, Johnson was allowed to drive himself home in the unmarked LBPD vehicle his Commander allowed him to improperly keep as a personal car, even when off-duty and not on call. Employees and customers at Crow's Cocktails (where Johnson had been drinking just 10 minutes before the accident) describe Detective Johnson being a habitual drinker with his drink of choice being a "pint glass full of straight vodka with a soda side."

One patron recalled once asking the detective if he ever worried about getting a DUI, only for Johnson to reply, "not in the car I'm driving."

That incident was not the first time or the last time Johnson would make the news, and not for heroics or earning commendations.

In early 2017, a fellow homicide investigator alleged that Johnson took part in the investigation of an officer-involved-shooting while "smelling of alcohol and possibly intoxicated." The allegation was made to homicide supervisors, Sgt. Megan Zabel and Sgt. Robert Woods, but Johnson was not disciplined. In fact, it was Detective Bigel (the colleague that reported Johnson) that ended up being transferred out of homicide in retaliation for reporting the misconduct.

Johnson is also the detective that is alleged to have botched the investigation of the 2014 death of Dana Jones. It is unknown if Detective Johnson's alcohol problem played a role in this failure of an investigation, but the investigation was certainly sloppy and incomplete regardless of the detective's sobriety at the time.

Lisa Jones dedicated herself to solving her sister's murder—after Johnson cleared her sister's husband of the murder by attributing Dana's death to a freak yoga accident. Lisa's investigation into her sister's March 2014 death is detailed on her website yogadeath.com and in her November 2019 book, "Blunt Force Yoga" (highly reviewed and available in paperback).

Detective Johnson's troubles continued after his alleged DUI. Months later, he and his partner were accused of coaching a witness in a murder case and conspiring to keep evidence from the defense—with the judge in the case writing a letter to Chief Luna stating, "the behavior of the detectives is appalling and unethical and inappropriate." The accused in that case was freed without having to stand trial, with the judge holding Johnson and his partner to blame for the botched case.

Before the judge could take steps to see that detectives were added to the L.A. District Attorney's Brady List (the list the D.A. maintains of officers so tainted that they can not be put on the stand to testify due to the disclosures of past misconduct that have to be made to the defense), two LBPD officers visited the judge in her chambers and somehow convinced her to change her mind. The whole affair is murky and unexplained to this day, but at least this fourth incident finally got Detective Johnson transferred from Homicide.

In his reporting and commentary on the Todd Johnson DUI incident, Stephen Downing makes the well-supported point that the LBPD protects its own from internal investigation and stonewalls reporters.

Mr. Downing's March 2018 article, Misplaced Loyalty, recounts a meeting Downing had with LBPD Internal Affairs regarding the DUI incident and the insight Downing had into the incident. Before the interview, Mr. Downing had established that he would not be giving up his whistleblower sources, but would be more than willing to "assist in ferreting out the depth of misconduct involved."

During the 90 minute interview, Mr. Downing was" left with the impression that Lt. O'Dowd and the sergeant [Dominick Scaccia] were more interested in challenging the quality of the information in the column rather than getting to the real truth of Detective Johnson's alcohol problem and the LBPD's broken organizational culture of cover-ups, cronyism and retaliation."

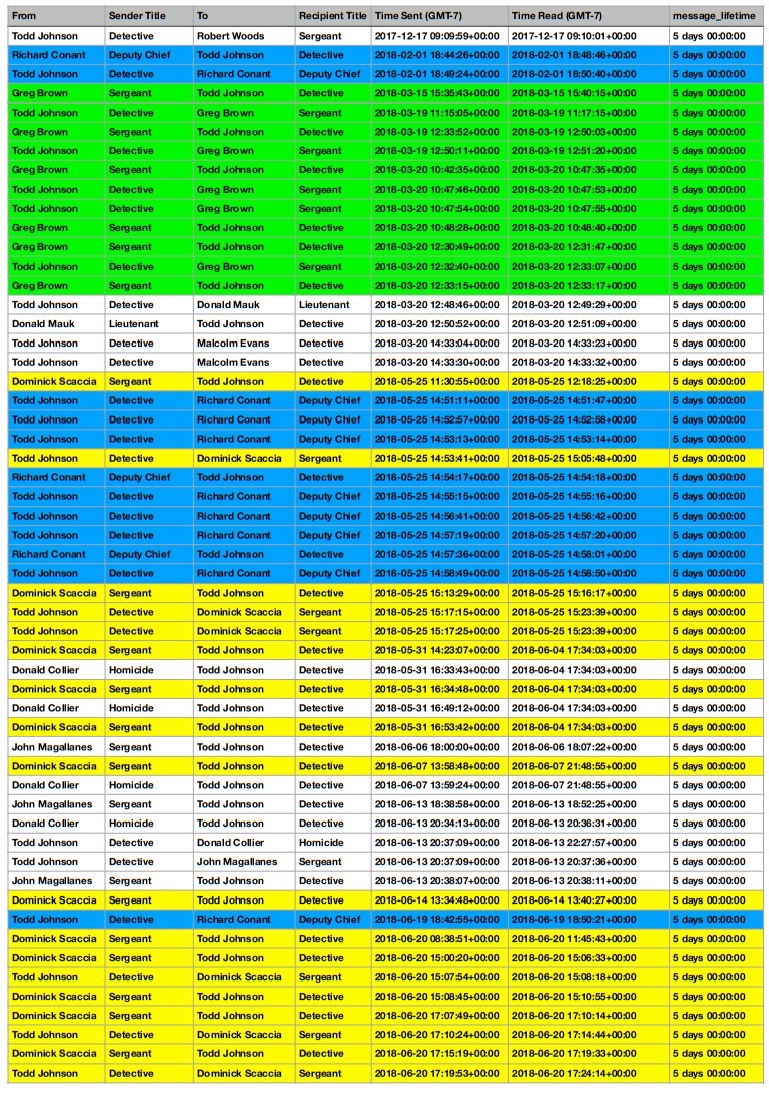

The day after Mr. Downing published "Misplaced Loyalty," a series of TigerText messages were exchanged between Detective Johnson and Internal Affairs Sergeants Greg Brown and Dominick Scaccia—the first messages Johnson had ever exchanged with either Sergeant.

In the following months (as the IA investigation was likely on-going), Johnson would exchange 80 messages with the two IA sergeants—mostly with Scaccia, who we know from Downing's reporting was investigating Johnson.

One potential explanation for these messages could be that they were routine. However, in over three years of using TigerText, Johnson had never exchanged a single message with either Internal Affairs Sergeant.

To make matters more suspicious, neither IA Sergeants Brown nor Scaccia had ever sent a TigerText message to anyone before March 2018. Once the Johnson investigation began, they exchanged dozens of messages with Johnson. Their other communications in this period suggest who else may have been involved in any cover-up.

It was after the DUI incident that then-Deputy Chief of Investigations Richard Conant (retired) first exchanged TigerText messages with Johnson. They had a brief back and forth after Downing's February article on the incident. Later, the second article and conversations between Johnson and the IA Sergeants would seemingly trigger subsequent messages from Johnson to Conant. Scaccia and Conant would exchange 18 messages during the last six days of May 2018 and 30 messages in June 2018

Deputy Chief Conant had worked his way up the ladder from IA Sergeant to IA Lieutenant, then IA Commander, and finally to Deputy Chief of the Investigations Bureau. From his messaging pattern, Conant still seems to be involved in IA investigations. Also involved in the early messages to the IA Sergeants was then-IA Commander Lloyd Cox—the officer who had set up TigerText for the department.

OTHER USES BY INTERNAL AFFAIRS

IA Sergeants Brown and Scaccia were not the only IA investigators using TigerText to communicate about cases. It seems most IA officers used the app. There are also group messages that obviously relate to IA investigations. While there is no message content in the metadata, when someone started a messaging group, the group name made it into the metadata. Most of the group names just are a list of the participants, but a few were given unique names.

One such group was formed in April 2015 and was named "IA Case," with the participants being Commanders and Deputy Chiefs.

Another group named "OIS/Homicide/Cmdr/Lt" was formed at the end of May 2015. As the name suggests, the group consisted of Commanders and Lieutenants—with the topic of conversation was most likely an Officer-Involved-Shooting. This is a type of TigerText use that was never explored in the BB&K report.

Another interestingly named group was the "Common Sense Squad," which exchanged 153 messages from Nov. 16 to Nov. 19, 2015. The members were Lt. Douglas Davidson, Lt. Joseph Gaynor, Lt. Wally Hebeish, Lt. Kristopher Klein, Lt. Steve Lauricella.

Isolating the messages of IA officers shows not only extensive use of the secret messaging system and messages with those under investigation but also patterns of use that spike following some officer-involved-shootings and in-custody deaths.

Our hypothesis is that much of the TigerText use is related to shooting review boards and other official misconduct hearings. More information is needed to test this hypothesis, and PRA requests are pending and overdue for documents showing the dates and participants of such hearing.

LONG BEACH JAIL OVERTIME SCANDAL

Another Downing article on an LBPD scandal stems from an Oct. 5, 2017 anonymous letter he received. The letter recounted allegations of misconduct at the city jail that had been made internally in July 2017 but never investigated by the department or city.

According to Mr. Downing, the letter "described in detail the specifics of the 'toxic environment' by reciting accounts of failed leadership, deputy-chief-level favored employees being untouchable, lack of training, callous, retaliatory supervision and unearned crony-related promotions." The letter ended with a description of "on-going criminal conspiracy – condoned and practiced by top-ranking LBPD administrative personnel – to commit overtime fraud."

The two city employees named in the letter are Sergeant Louis Perez and Tom Behrens (the civilian jail administrator). Behrens was a TigerText user, one of the more infrequent ones at that. In fact, it seems the only real use he had for TigerText was related to the misconduct allegation made against him.

Behrens was not a big TigerText user, only sending or receiving exactly 100 messages over 27 months. However, in a 30 day period starting in July 2017 (when the internal whistleblower complaint was made), Behrens exchanged 30 messages with Security Services Commander Joel Cook. He would continue to exchange messages with Cook until September 2017.

Behrens would then take an eight-month break from sending or receiving any TigerText messages. He did not start messaging on the system again until May 2018, when he would begin a regular exchange of messages with Lt. Donald Mauk and Commander Jeffrey Berkenkamp that would continue until TigerText use was discontinued in September 2018.

The jailhouse OT scandal is still the subject of an on-going Downing/Beachcomber investigation. The LBPD is yet again stonewalling Downing's public records requests, with the Beachcomber having retained Long Beach Civil Rights attorney Thomas Beck in its quest for documents related to the cover-up.

Until those are produced, the metadata traffic of the Jail Administrator Tom Behrens is the best record we have of communications related to that whistleblower complaint.

QUESTIONABLE INDEPENDENCE

BB&K independence was questioned from the very beginning for a good reason. They had worked on two matters critically important to the city's power brokers as part of an on-going contract for legal advice with the city for $100,000.

As reported by the Beachcomber, it was BB&K the city hired to file a writ of mandate to force Juan Ovalle (the mayoral appointed opposition writer) "to water down the ballot arguments he filed opposing Mayor Robert Garcia's Measure BBB initiative to extend term limits." A review of city contracts shows BB&K also advised on the critical 2016 sales tax ballot measure campaign.

At the time BB&K was hired for the TigerText investigation, Carlos Ovalle, Executive Director of the community group People of Long Beach said, "the independent review is about as independent as the Dodgers bringing their own umpire to the game or a defendant bringing his own judge to the trial."

CheckLBPD couldn't agree more—finding it ethically questionable, and a squandering of both taxpayers' funds and the best opportunity there was to conduct a true investigation.

Based on what CheckLBPD has uncovered, the past $100,000 relationship between BB&K and the City is small potatoes compared to the business the city sent BB&K after the favorable report.

Six months after turning in the TigerText review, BB&K landed the first of two very lucrative city contracts they would receive in 2019. The first contract started out at $200,000, before the contract was amended to cap billing at $400,000, then amended a second time with a billing cap of $600,000. The $600,000 was to represent the city in a second round of litigation with the owners of the Princess Inn.

As lucrative as $600,000 is, BB&K's other post-TigerText contract with the city could be even more lucrative. As of October 2019, BB&K is the city's new disclosure counsel (the lawyers who handle the required disclosure made related to bonds issued by the city). The contract is open-end, with BB&K handling all required disclosures through 2023. Hourly billing rates are set at between $470 and $580 for the three attorneys listed in the contract.

BB&K's TigerText report was well-received by the city government, with the report being publicly released and trumpeted as a vindication of the LBPD's actions. The treatment the BB&K report received contrasts markedly with another independent report commissioned that wasn't as favorable.

In 2017, the LBPD hired the International Association of Chiefs of Police to provide a systematic evaluation of the management and operation of the LBPD. In 2019, the city canceled that contract before the report could be issued and withheld the final half of the $96,000 payment. The city then fought in court to keep the 122-page report from seeing the light of day. As usual, it was the tenacious reporting of Stephen Downing that allowed this public document to actually be seen by the public.

CONCLUSION...

There was a lot that could have been investigated but wasn't by BB&K. The city should not now be rewarding them for the "independent" "investigation" on the taxpayers' dime after they so failed the people of Long Beach.

That's it for now, but this is an on-going project. Crowdsourcing is very welcome. There are likely other incidents and investigations from 2014 to 2018 that the TigerText metadata can shed light on.

If you have any tips regarding TigerText, or incidents you would like help comparing to the metadata, please contact CheckLBPD.

Questions, comments, or tips can be directed to Greg@CheckLBPD.org (encrypted on our end with protonmail)

This article was written by Greg Buhl, a Long Beach resident and attorney.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Feel free to distribute, remix, adapt, or build upon this work.